st. lawrence university magazine | fall 2014

2

3

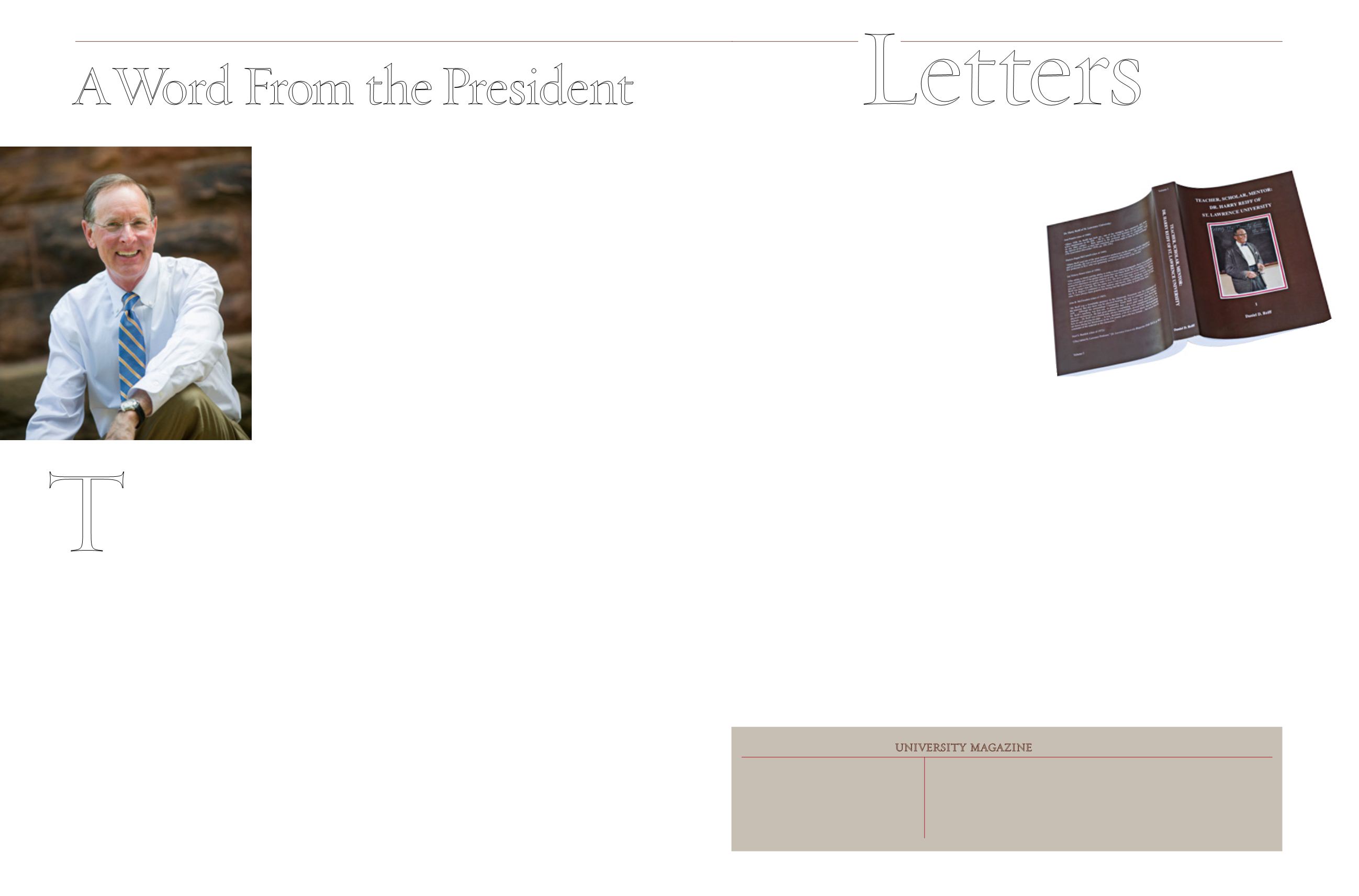

Living with Harry

I want to most heartily recommend

Daniel Reiff ’s book on his father, Pro-

fessor Henry Reiff,

Teacher, Scholar,

Mentor

. It is a wonderfully rich book,

full of photographs and letters and

other documents that give a deep

and wide-ranging sense of Harry and

his multiple achievements and his

personal life.

Reading the book, I felt I was living

with Harry and his times, culminat-

ing in his early years at St. Lawrence,

bringing the University alive, too. I

roomed in the Reiff house at 84 Park

Street in the 1950s, when I was an

assistant professor of English at St.

Lawrence, and can testify to Harry’s

devotion to the University.

Edward Clark | Medford, Massachusetts

The writer is professor of English,

emeritus, at Suffolk University. The

book about Professor Reiff is available

from

brewerbookstore.com.

to create the Adirondack Park Agency

to ensure that no large-scale develop-

ment such as this would be on the park’s

horizon. There will forever be a lot of

Peter’s spirit in that Grasse

River we fought so hard to

protect.

Richard Grover | Canton,

New York

In the days of

housemothers

I was touched by the remem-

brance by Jane Wendt Wilson

in the Winter 2014 Class Notes

for 1957 concerning Mrs.

O'Brien, the housemother at

Gaines House.

Elizabeth

“

Bessie

”

O'Brien was my

grandmother. She was born in 1892, and

could remember celebrations marking the

end of the Spanish-American War. In the

late 1940s, after raising two daughters, she

started a career when most people would

be thinking about retirement: she came to

Canton to become a housemother at St.

Lawrence, where one of her daughters (my

mother) had graduated in the Class of 1943.

The stories recounted in the note certainly

ring true: Gram had no-nonsense standards,

and when she was in charge, she usually

got her way. She eventually retired for real

around 1960, and lived well into her 90s.

Thank you for the unexpected reminder

of how people can touch other people's

lives, even so many years later.

Michael Sheard | Memphis, Tennessee

The writer is Rutherford Professor

of Mathematics, Emeritus.

ST. LAWRENCE

university magazine

volume lx111

|

number 4

|

2014

St. Lawrence University does not discriminate against students, faculty, staff or other beneficiaries on the basis of race, color, gender, religion, age,

disability, marital status, sexual orientation, or national or ethnic origin in admission to, or access to, or treatment, or employment in its programs

and activities. AA/EEO. For further information, contact the University’s Age Act, Title IX and Section 504 coordinator, 315-229-5656.

A complete policy listing is available at

www.stlawu.edu/policies.Published by St. Lawrence University four times yearly: January, April, July and October. Periodical postage is paid at Canton, NewYork 13617

and at additional mailing offices. (ISSN 0745-3582) Printed in U.S.A. All opinions expressed in signed articles are those of the author and do

not necessarily reflect those of the editors and/or St. Lawrence University. Editorial offices: Office of University Communications, St. Lawrence

University, 23 Romoda Drive, Canton, NY 13617, phone 315-229-5585, fax 315-229-7422, e-mail

nburdick@stlawu.edu, Web site

www.stlawu.eduAddress changes

A change-of-address card to Office of Annual Giving and Laurentian Engagement, St.Lawrence University, 23 Romoda Drive,

Canton, NY 13617 (315-229-5904, email

slualum@stlawu.edu)will enable you to receive St.Lawrence and other University mail promptly.

Editor-in-Chief

Neal S. Burdick '72

assistant editor

Meg Bernier '07, M '09

art director

Alex Rhea

associate art director

Susan LaVean

Design director

Jamie Lipps

photography director

Tara Freeman

News editor

Ryan Deuel

class notes editor

Sharon Henry

A memory of Peter Van de Water

In early spring 1972, I received a call

from the president of the Horizon Cor-

poration in New York City. He wrongly

assumed that I, as director of planning

for St. Lawrence County, would be

pleased at the news of Horizon’s purchase

of 25,000 acres of Adirondack forestland

in the Grasse River headwaters. Horizon’s

plan was to build dams and golf courses

and subdivide the land into thousands

of building lots to be sold nationally to

private investors.

A furor of state and national sig-

nificance developed over the proposed

scheme. Local newspapers expressed

unbridled support for the proposal,

which, it was asserted, had the promise of

transforming this Adirondack “waste-

land” into a magnet for new home buyers

and recreation seekers. But a groundswell

of opposition also quickly emerged, and

it was through this controversy that I

met Peter Van de Water ’58, whose death

was noted in the summer issue of this

magazine.

A decision was made to organize against

the proposal; Citizens to Save the Ad-

irondack Park was formed and Peter was

elected its president. The CBS Evening

News ran a story in which a canoe ap-

peared, quietly slipping through still

water, Peter in the stern, talking about

the value of the Adirondack wilderness.

It’s the vision of Peter in that canoe that

lingers most in my mind…a man at

home in the wilderness environment he

loved, arguing for its protection.

The battle, which we won, played a

huge role in New York State’s decision

Are You Going?” reminds me of what we

believe St. Lawrence students may appre-

hend as they come casually into the

Quad from stone steps or a sitting wall:

“O do you imagine,” said fearer to farer,

“That dusk will delay on

your path to the pass,

Your diligent looking discover the lacking,

Your footsteps feel from

granite to grass?”

they are indeed wayfarers, of mind

and dream, passing with diligent looks

“from granite to grass.” And the grass

becomes a consulate of paradise.

College courtyards and university

quadrangles perpetuate the green imagery

found in the oldest conviction that an

academy of learning requires a time and

place of ample leisure. Only in a fleeting

moment of paradise is it possible for the

mind to strive for freedom and, ultimately,

to have a chance of surpassing the mind’s

limits. The motive of the Quad in all its

activities today—whether frisbee games

or chairs in a circle—is freedom; and once

we have known that, we ought to fear its

loss. I know this from an office window

overlooking the Quad, for there is no more

beautiful sight than a student sprinting

across the grass, hands outstretched under

a long-tossed ball. The young legs run

as if the earth has no end and the land is

forever green. The unbound, measureless

free play of intellect still matters.

The Quad expresses its paradise motif

in which students dream of themselves

as better than they are. The Quad is a

beloved memory for us of other years and

for no better reason than it recalls a free-

dom that for the rest of our lives we are

somehow trying to regain. The memory

of walking across the Quad in sunshine

or moonlight, of heeding the horizon line

of the Adirondack hills, is akin to what

Josiah Royce once described as the pause

in the day given as “a principal glimpse

of the homeland of the human soul.”

n

—WLF

he cherished st. lawrence

Quad is curiously undivided,

tracing no paths, labyrinths

or walkways across its plane

geometry. This square field

is also notably different from

the equivalent flat places on

other American campuses for its unadorned

interior and exclusive greenness. Its simplic-

ity is exceptional. The Quad features no

fountains, statues or structures. There is no

monumental gate or obvious entry point,

which makes sense because there is no brick

wall or iron fence defining its perimeter.

It is just an expansive main lawn, slightly

tilted to the sunrise. Its unusual subtlety,

nevertheless, is loaded with moral signifi-

cance and community meaning.

Many American colleges were intention-

ally placed on the edge of the rural wilder-

ness, often before there were good roads to

get there. St. Lawrence’s history took root

in this venerable tradition. On the surface

of this frontier heritage, these choices of

location seem prudent because land was

cheapest there and the ideal of undistracted

learning was best accomplished when stu-

dents stayed at impossible distances from

denser, hurried populations.

There is much more to this story, however,

than older economies can explain. In fact,

the St. Lawrence Quad reflects a deeper

and longer perspective about the workings

of a college, something more than a once-

quaint remnant of pastureland.

In the earliest years of building American

colleges, the founders always aspired to the

conditions of paradise. In their design and

purpose, the builders wished to leave bold

statements to their posterity, though usu-

ally without the means of grand architec-

ture. No matter what building ambitions

were imagined, the first colleges reserved

in their plans some untouchable, unbuilt

ground as a central educational necessity.

They gave priority to their green spaces.

The dream that a wilderness contains

within it “paradise” is very old, actually

traceable linguistically and mythologically

to Assyrian and Persian sources; the word

“paradise” itself is derived from an ancient

tradition of setting aside a park-like royal

enclosure. The idea of paradise as a garden

later emerged in the more familiar narra-

tives set down in Jerusalem, Athens and

Rome. The belief that in the midst of an

incomprehensible wilderness there can be

a garden, a place of sanctuary, was a power-

ful physical and metaphysical theme of

unexpected variation; it gave hope through

centuries of inescapable, hard human

experience in the chaos of a wasteland.

Paradise seems a far country, yet never

far from home. From desert monasteries

to medieval universities, the quadrangle,

the cloister, and the close were ways of

remembering the quest for meaning in

the wilderness. To find the serenity and

freedom of a garden, the richly explored

premises of both Dante and Milton,

brings together a thematic coherence that

is our institutional extension of paradise,

a place as simple as a lawn but also a place

to find a reliable corner of one’s mind.

W. H. Auden’s 1931 poem “OWhere

AWord From thePresident

T

From granite to green—the Quad’s purpose