18

19

movie: the student ship steaming toward a year in France—

a romantic comedy, wouldn't you think?

Other articles through the 1980s surprised me with how strong

the tradition proved, how little changed over the first 25 years:

An initial period in Paris, then off to the thoroughly modern

buildings of the University of Rouen, excursions to Mont-Saint-

Michel and the Loire, and the glorious year-end trip to the south

of France. Students took eight courses, which lasted all year long,

including the famous optional course, in regular university classes

shoulder-to-shoulder with “real” French students. And, of course,

there were the family homestays, since the beginning the pillar

of our program: my French brother, my French mother, said the

students back then, and say the students still today.

In a series of remarkable articles from 1964, ’65 and ’66,

student writers recount in

The Hill News

their adventures in

France. I recognize it all: the university buildings are filthy and

full of smoke; French students lounge in the corridors and dis-

tribute political pamphlets, showing little inclination to practice

intercollegiate sports or go to fraternity parties. Our students

rave about the pastries, the cheeses, the warmth of French fami-

lies. And then, as now, they love to travel. France's generous

vacation schedule permits excursions all over the continent.

Much has remained the same, but many things have changed.

In 1966, 34 students went to France; this fall we are sending

eight. Half of those in 1966, 17, bought scooters; others regu-

larly hitchhiked. Today, I hazard to say that none will purchase

scooters and none will hitchhike. Those perilous transportations

have long since gone the way of the

Aurelia

.

By the mid-90s, most students no longer wanted to stay the

year, but only a semester, so we let that happen. The opening

Water Lilies on Walls

By Shayla Snyder Witherell ’11

Reflections on First-Year Encounters

with the French

The Franco-Laurentian

Connection

By Roy Caldwell

fifty years in five minutes

emories from France return to me outlined in

Monet’s impressionist brushstrokes. The weathered

grey gargoyles and saints of the Cathédrale Notre-

Dame de Rouen glared at me from their perch on

the multi-faceted façade, their countenances becoming warmer

as winter days lengthened to the brighter days of mid-spring.

When I think of Paris and of Giverny, the water lilies float on

walls of the Musée de l’Orangerie and reflect in the water under

the Japanese bridge. The iconic cliffs at Étretat, their mottled

white, black and grey layers, tower above the blue sea lapping at

their base. At the end of my four short months on the Global

The following is adapted from remarks offered by French professor

Roy Caldwell at a banquet during the France Program’s “affinity

reunion” on campus on May 31, 2014. He began by explaining that

in order to learn about the program’s early history, he “climb(ed)

into the stacks of ODY, where I consulted dusty

Gridirons

and

yellowed copies of

The Hill News.

”

hese, I think, have been the directors: Andrews,

Carlisle, Jones, Pommerat, Garrity, Pierce, van

Lent, McHugh, Dargan, Caldwell, Stipa, Romey,

Jockel, DeGroat, Weiner. The teachers have been

much more difficult to recall. Little trace remains

of them in University publications. Only some

names survive. M. Virolles, our first literature

professor, received an honorary degree from St. Lawrence in 1980.

I heard some of you talk about him yesterday.

Then my memory brings forth the names of Messieurs Bâtard,

Javet and Maurice; Madame Orange, still guiding our students

through the labyrinth of French grammar; Mlle. Turgis, Madame

McDonell, and Messieurs Le Brozec and Chérif Aidara. I learned

of a certain M. Noisette de Crossard, whom I never knew but who

left a noble impression on those students who worked with him.

But especially I remember, as do many of you, the late Éliane

Pigache, heart and soul of our program from the early ’70s

until the first years of the current millennium. Let me ask you

to recall, too, her husband, the good Dr. Pigache, Bernard, the

most generous and considerate of all human beings. How I wish

he were here tonight.

In

The Hill News

of May 7, 1964, an article by Carole Ashkin-

aze ’66, a member of the initial program, reports that Professor

Oliver Andrews of the Modern Languages Department had just

returned from a six-week tour of France, where he visited other

programs in the hexagon, met with city and university officials

in Rouen, and planned the course of study for the St. Lawrence

students arriving in the fall. Dr. Andrews was interviewed by

the editor of the newspaper

Paris-Normandie

, who described

St. Lawrence as “one of the most famous American universities,”

and hailed the participants in the program as “brilliant students.”

The Franco-American collaboration was off to a great start.

Another article reports that 25 students had been selected for

the “JYP” and that Dr. Andrews, accompanied by Dr. Robert

Carlisle of History, would direct. It further notes that the group

would be departing in early September for Le Havre–now get

this–aboard the

Aurelia

, a student ship. The Atlantic crossing

lasted nine days, and there were French language courses every

morning. How the students of this first program spent the rest

of their nautical and pedagogical experience has been lost in the

mists of time. I cannot fathom why no one has made this into a

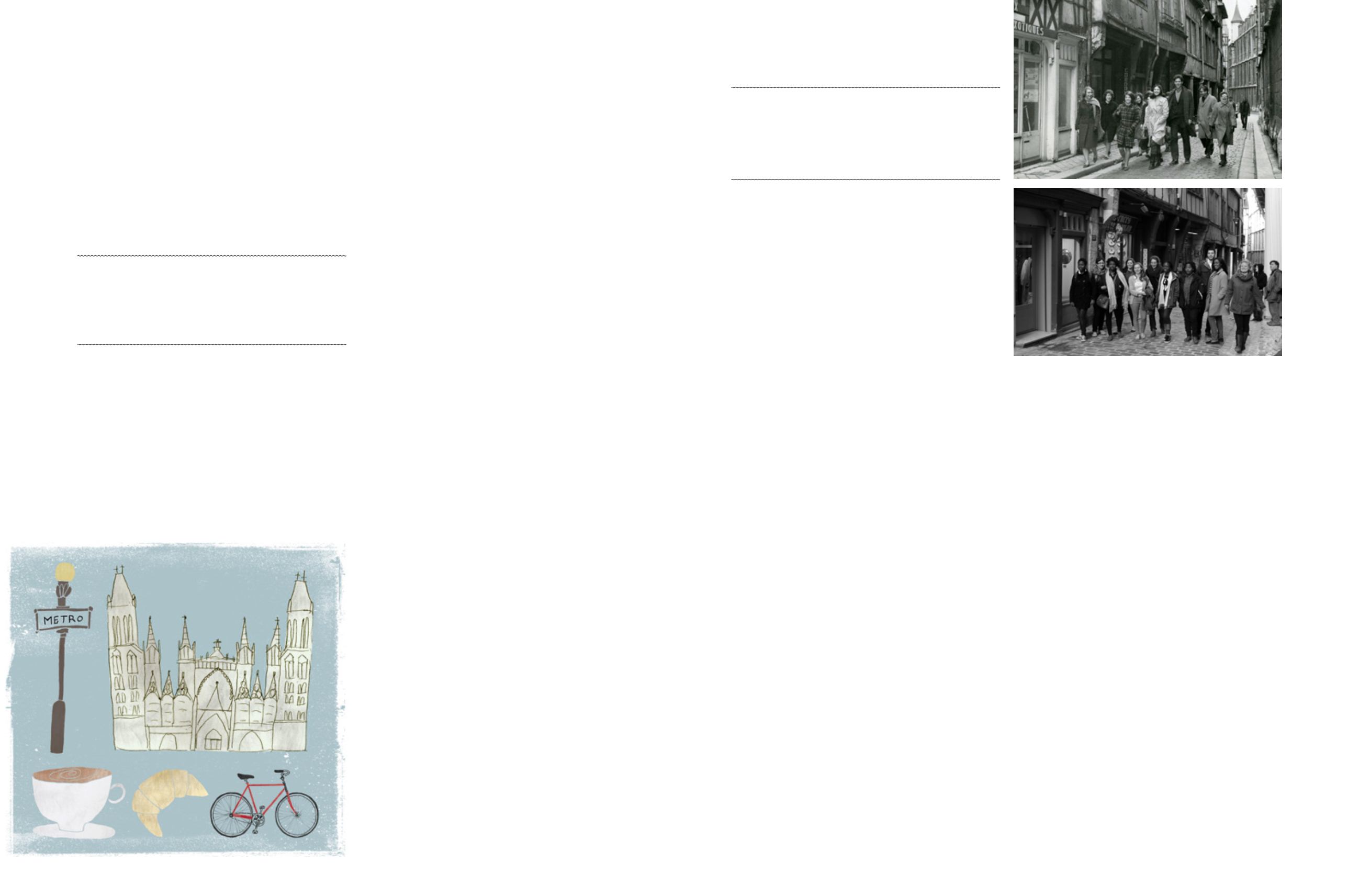

In his France Program Reunion Dinner remarks, Prof. Roy Caldwell

commented that “Much has remained the same, but many things

have changed.” These pictures, taken on Rouen’s Rue Saint Romain

in 1964, the program’s first year (top), and 2014, portray that truth.

bottom photo: Tim Wheeler '15

T

In recognition of all of this, in the next few pages we acknowledge

the two milestones that were at the hub of this year’s Reunion

Weekend, the 50th anniversary of that first program in France

and the Kenya Program’s 40th.

What lies ahead? Long-term, we can foresee St. Lawrence

adding more programs in more countries, and even higher

percentages of students taking advantage of these enriching

opportunities. As the world grows ever smaller in ever larger

ways, we will be able to say with ever more certainty that the

education St. Lawrence provides is truly global.

M

Francophone First-Year Seminar, I hiked to the top and stood

on the precipice of those cliffs. I realized then how fleeting our

time is, compared to the millennia sketched in the stratigraphy

of that weathered chalk.

I was not always at such ease. With the 50th reunion of the

France program, I was compelled to read my journal of those

four months. Six years had flown by since I had returned home

and put it away, enough time to be critical of and fascinated by

the thoughts of my 19-year-old mind as I worked through the

challenges of living abroad.

My second night in Québec, I found myself wandering the

foggy, slush-filled streets. Weighted down with soggy pant legs,

elementary French and rising panic at being lost, I wondered

if I had made the right choice. Maybe a small-town girl from

rural New York State wasn’t meant to try this experience. Safely

in the home of my Québécois family, frustration oozed onto my

journal page; on the verge of tears, I scribbled, “I feel clueless!”

My first-ever airplane journey shortly after that night took me

to Rouen. I decided to walk as much as I could. I walked half an

hour up the narrow, winding streets to

la fac

at Mont-Saint-Aig-

nan every morning, choosing the Rue Raffetot, a steep incline that

left me breathless and matched my uphill battle with the French

language as I struggled to be myself around my host family.

In time, both my understanding and expression of French

and my endurance for climbing the hill improved. On Sunday

afternoons in the Place du Vieux Marché, I was symbolically

warmed by the proximity of the historic flames under the cross

where Jeanne d’Arc was burned. In Paris in March, I walked for

miles one chilly yet sunny afternoon with a map as my only com-

panion, exploring the Latin Quarter. On a Saturday morning in

April, I connected with my host mother as we explored Rouen’s

Musée de la Céramique together and laughed at a silly joke that

I had come up with. The terrified girl on the dark streets of

Québec who couldn’t ask for directions in French had changed.

One semester is fleeting in the history of the 50 years of

St. Lawrence’s oldest international study program, as is 50 years

in the history of Rouen, where Monet painted the cathedral built

centuries before his time. Yet the transformational powers of the

program, and all of St. Lawrence’s off-campus programs, lie

in those transferrable acquired lessons that last a lifetime.

I wish I could say that my desire to go to France was more

profound than a superficial interest in Monet, Jeanne d’Arc and

the beauty of the French language. I often wrote in my journal,

“I can’t believe that I am really in France,” after visiting iconic

tourist attractions. Now I realize that those sites are just added

bonuses, landmarks on the canvas surrounded with the skillful

splash of light and dark colors. The challenges, the successes and

the lessons in that place are the final composition, a priceless

piece commissioned from choosing to walk the steep uphill

climb that is studying abroad.

Shayla Witherell is St. Lawrence’s assistant director of donor

relations. Her Global Francophone First-Year Seminar took her

to Québec, France and Senegal in spring 2008. Her story about

two “Laurentian for Life” couples who still enjoy skiing appears

in the Sports pages of this issue.