Back in East Africa

By Dekkers L. Davidson ’78

"We’re

over Africa…you can see the coast of Tunisia.” Indeed,

under the moonlit sky, I could see the silhouette of North

Africa against the Mediterranean Sea some 30,000 feet below

our Nairobi-bound plane.

"We’re

over Africa…you can see the coast of Tunisia.” Indeed,

under the moonlit sky, I could see the silhouette of North

Africa against the Mediterranean Sea some 30,000 feet below

our Nairobi-bound plane.

The words of excitement and anticipation could have been mine;

instead they were those of my son, Kyle ’06. He was heading

to the spring 2004 Kenya Program (KSP); his experience in Africa

was just beginning. That was where I had finished my St. Law-rence

education as a senior—an extraordinary semester in a

place I’d never forgotten.

That experience was coming back into sharp focus as we approached

our landing, and there was one we hoped to re-create together—the

climb to Kilimanjaro’s summit, which I had accomplished

as a student on the program in 1978. We and the mountain would

have a short visit together before the semester would begin

and I would return home.

A Different Nairobi. While I expected things would be different,

I wasn’t fully prepared to see how much Nairobi had changed.

The city sprawled in all directions and skyscrapers loomed

where parks and homes had stood 26 years before. Traffic overwhelmed

the same road system that had existed in the 1970s; cars, buses

and matutus (small trucks that pack a dozen or more into their

small cabs) crawled through the city at all hours of the day.

|

| At Gilman's Point in 1978,

the St. Lawrence group includes, from left, Dekkers

Davidson '78, their guide, Peter Crossan '78, Joan

Flagg '79, Kathy Brown '79 and Kathy Flynn '79. |

Evidence of a new and tragic development, AIDs, was everywhere—perhaps

most poignantly in the buses marked by signs indicating they

carried AIDs victims or orphans. It seemed profoundly unfair

that a continent that has had so little had been further battered

by such a horrible disease. And yet, people smiled, laughed

and shouted amid the bustle—signs of life were everywhere

despite the chaos, confusion and hardship.

The former KSP compound in Westlands, now guarded by a large

concrete wall, had become a dilapidated apartment; the St.

Lawrence campus had moved years ago to a quiet and beautiful

site on Nairobi’s outskirts in the town of Karen, located

in the Ngong foothills. But some things seemed unchanged: the

favorite student hangout at the Norfolk Hotel near the University

of Nairobi seemed as it was years ago, as did the city market

where the merchants hustled us with the same “special

for you” deals that had made us laugh as students.

My African Family. My family home stay had been a very special

highlight of my experience; I’d lived just outside Nairobi

with the Mwakazi family. We’d remained in regular contact

by mail and e-mail; our reunion at their Langata home had been

a long time in the making. Reuben, who was then a playful 5-year-old,

was now a grown man with a career in the lumber business. Grace,

who had graduated from St. Lawrence in 1990, was married with

a son. And Mama Mwakazi was still the same happy and lovely

person I had always remembered. But sadly, Johnson, my home

stay father, was gone, having passed away suddenly in 1993—the

same month in which I had lost my father.

Africa’s Enduring Treasure. In 1978, our trip to Ngorongoro

Crater had been blocked at the border by tourist squabbles

between Kenya and Tanzania. But this time, nothing, not even

a tedious six-hour ride on a bumpy dirt road, would prevent

us from visiting this wildlife sanctuary on the Serengeti Plain.

Ngorongoro is a treasure chest of Africa’s most impressive

wildlife: elephants, lions, rhinos, gazelles, wildebeest, cheetah,

hippos, flamingos were everywhere inside this extraordinary

15-mile-wide crater. Nearby Lake Manyara showcased huge herds

of giraffe and elephant; at one point, nearly 100 elephants

lumbered by our vehicle, hardly giving us a nod. It was reassuring

to see so much wildlife and to know the game had been protected – something

that had been in doubt in the 1970s.

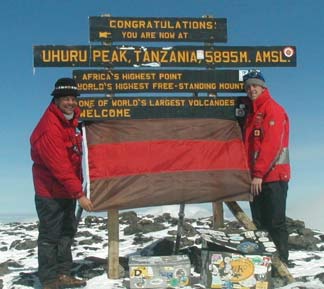

From the Equator to the North Pole. The highlight of our short

trip would be the long climb to Kilimanjaro’s summit,

which stands at 19,350 feet above sea level, looming over the

plains of East Africa. I’d made the trek with five classmates,

reaching the summit on February 28, 1978—it had seemed

so easy. As we’d done then, Kyle and I based our expedition

at the Kibo Hotel and were provided two experienced mountain

guides and a crew for the five-day, 70-mile trek.

The climb, sometimes called the “shortest walk from

the Equator to the North Pole,” would take us through

nearly every climactic zone on Earth. We’d start in mountain

meadows, climb through rain forests, trek above the tree line

across barren desert, and ascend on volcanic scree before reaching

the summit. Our January climb would be in the “dry season,” and

good weather was expected. Instead, rain, hail and snow fell

on each day but the first (the exact opposite to the weather

during our earlier climb). Nevertheless, we had done enough

hiking and climbing to deal with the conditions and made camp

each night without much difficulty. And we had enough good

visibility between the storms to see the imposing summit above—so

we could see what lay ahead.

Or so we thought. The final ascent of Kiliminjaro began around

midnight with the goal of being on the summit by sunrise. But

on this moonless night, the zero-degree temperature and thin

air turned our strides into a slow shuffle. The cold had been

expected, yet we were surprised to find our water bottles partially

frozen, discouraging us from drinking as much as we needed.

The guide’s hot chocolate held far more appeal, though

it did not provide much hydration. Kyle, just recovering from

a broken leg suffered in a rugby match a few months earlier,

needed my encouragement to keep going; the cold bothered his

legs and toes.

Our spirits soared with the arrival of the warm sunrise just

as we reached Gilman’s Point—the rim of Kilimanjaro’s

long-dormant volcano. With a clear blue sky, we could see Uhuru

Peak a couple of miles away—it was, we thought, easily

within reach. On my previous climb, we’d been shrouded

in snow and I had followed my guide blindly and rapidly to

the summit. From memory, I was certain it was just a 30- to

45-minute walk.

But the final climb, now under a hot sun, took a long and

tedious two-plus hours. When we reached Uhuru Peak we were

totally spent, and it was still only 9 a.m. But the snow that

I remembered was gone. Deforestation at the foot of the mountain

has been blamed as much as global warming. The top of Africa

had clearly changed, and some predict that the snow-covered

glaciers just below the summit may disappear entirely in another

25 years. (For more on this, see the story on page 44, on the

research being conducted by Doug Hardy ’79.) We took

a few pictures, used our satellite phone to call home to declare

our success (something unimaginable in 1978!), and began our

descent—just as a blinding snowstorm arrived. To make

matters worse, I’d become light-headed and dizzy—I

could not believe I was experiencing altitude sickness on our

descent. I suddenly realized I’d not drunk enough water.

As quickly and carefully as possible, we worked our way down

the mountain, mindful that most climbing injuries occur on

the more dangerous descent. And now it was Kyle’s turn

to help: he forced me to drink water and, along with the guides,

helped me descend. We found refuge at 17,000 feet in the Hans

Meyer Cave as the snow turned to hail and cold rain. By noon,

12 hours after our summit push began, we were back at our final

base camp and had changed into dry clothing and finally warmed

up.

The next day, under a deluge of rain, we finally made it back

to the Kibo Hotel and celebrated with our guides and crew.

We had followed the same itinerary as I had used in 1978, but

the experience had been a very different one—the weather

had humbled us and the changes to the summit had left a lasting

impression. But, it had been a thrill to raise the

St. Lawrence flag atop Kilimanjaro and to have shared this

experience with my son.

When we said our goodbyes, Josef, our assistant guide, told

us that his earnings from our trek would allow him to pay for

his child’s education for an entire year….reminding

us that small things can make a big difference in East Africa.

It was a lesson I remembered from years ago, and one that Kyle

would see borne out many times in the months ahead.

For a second time for me, and for Kyle, a second-generation

KSP participant, there had been an unforgettable experience

in East Africa.

St. Lawrence Trustee Dekkers Davidson lives and operates

a business in Concord , Mass.