34

35

on campus

st. lawrence university magazine | winter 2015

laurentian portrait

rience it and come at it from

different ways.”

As much as Reid has

been on his own personal

expedition creating his

works, he also hopes to

inspire others to let the art

move them emotionally.

“I’m striving for a sense of

feels to me like parenthood.

That’s why I do this; that’s the

feeling I’ve been looking for.”

Reid was the recipient of

a Daniel F. ’65 and Ann H.

Sullivan Endowment for

Student/Faculty Research

University Fellowship, and

he worked last summer

alongside Kasarian Dane,

associate professor and chair

of the Department of Art

and Art History, on his

project, titled “Mathemati-

cal Underpinnings.”

Reid’s art isn’t immediately

recognizable, especially to the

non-art expert (such as this

writer). His work involves

what he calls “geometric

abstraction,” and it can at the

outset look like simple shapes

repeatedly painted in different

colors on multiple canvasses.

Yet, as Reid expresses his

thoughts on color theory, as

he explains his process and as

he stands with you looking

fondly at his work, it becomes

apparent that this artist is on

a very deep and very personal

artistic journey.

“Geometric abstraction has

to be extremely simplistic,”

he says. “Yet, it has the power

and emotion that comes from

the fact that anyone can expe-

here’s something

immediately

noticeable to the

listener when

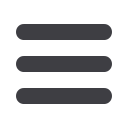

Reid Brechner ’15 starts talk-

ing about his artwork. At first

it might be hard to define,

but then it becomes readily

apparent: This young man

simply sounds way too old

for his age.

Reid speaks about his art

as if he were finalizing the

last chapters of his doctoral

dissertation. He talks about

how he spent last summer as

a University Fellow work-

ing up to 12 hours or more

in the Griffiths Arts Center,

ignoring the siren songs of

summer beckoning at the stu-

dio windows. And, he speaks

about his art with paternal-

istic pride, which makes the

listener proud for him and

the work that he’s done.

“Sometimes I have to work

out what’s at the top of

my mind,” says Reid, who

hails from Belgrade, Maine.

“Something starts bothering

me, and I can’t do anything

else until I work it out of my

head. Then, it’s weird when

I finish because I can look

back at it and know when it’s

done. I’m not a parent, but it

By Ryan Deuel

T

perpetual motion, and the

planes of color give these an

underlying sense of motion.

That makes it no longer

finite,” he says. “I want to

force people to look inside

themselves and not feel like

they have to feel a certain

way about it.”

n

“Geometric

abstraction has

the power and emotion

that

comes from the fact that anyone

can experience it and come at it

from different ways.”

Reid Brechner ’15

Reid Brechner ’15,

at the Intersection of

Math and Art

By josephine breen del deo '47

ar from attempting to turn back the

clock by writing this short com-

mentary about the digital

age of communication,

I suggest the oppo-

site: thanks to com-

puterization, the clock has

already been turned back

to a kind of hieroglyphics

which does not appear to

be enriching our lives by

advancing our percep-

tion, but instead has re-

duced us to a bare mini-

mum level of meaningful

communication.

The paroxysmofminutiae

that accompanies this process

has eliminated the imaginative

dimension of words to such an

extent that the world is contracted,

not expanded. Information alone is

not knowledge, a condition which can

only be acquired by the daily exchange of

ideas through language within an established value

system. Without this paradigm, education fails the

human equation and, thereby, its mission.

Today, we are so wholeheartedly engrossed in the

electronic technology governing every aspect of our

lives and civilization that we have permitted the

placement of computer screens throughout the public

elementary school system and even, in some cases, in

the pre-school classroom. At the same time, we have

reduced or removed the teaching staff that is meant

to guide and interpret the information that each child

receives. Further, we have exposed the adolescent

population to violent and increasingly ubiquitous

images in “virtual reality” on the digital screen. These

often present disturbing situations to impressionable

minds and occasionally trigger tragic behavioral

aberrations, as we have seen all too often.

Moreover, we have created an almost

complete addiction to cell phones

and their clones. It is not absurd,

therefore, to suggest that we

should monitor our appetite

for gadgetry.

The computer has offered

us astonishing advantages

in many regards, but the

advantages of “doing busi-

ness” with greater speed

and efficiency have not

been matched by a cir-

cumspect attempt to elimi-

nate the most dangerous

invasion of privacy on almost

every level that mankind has

ever known. Why have we, as a

society, so quickly abandoned our

cultural past based on the spoken

and written word, which has historically

promoted serious and extended thought and

philosophical perception? In this regard, it might be

beneficial, not only for the contemporary student

at St. Lawrence but also for all of us, to read Her-

man Melville’s story “The Bell Tower,” wherein may

be discovered how a great writer examines human-

kind’s perennial subjugation to improperly assimi-

lated and poorly controlled invention.

n

Abandoning the Spoken Word

We welcome your submissions for “First-Person.” They should be no more than 500 words and should connect with an

aspect of your lifelong experience with St. Lawrence University. For consideration, please email

nburdick@stlawu.edu.

F

Information is

not knowledge,

which can only

be aquired

by the daily

exchange of

ideas through

language.

,,

,,

Josephine Del Deo is a poet, fiction

writer, essayist, art historian and

1947 honors graduate of St. Lawrence.

Her memoir,

The Watch at Peaked Hill

, is

soon to be released by Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.

She lives in Provincetown, Mass.