Exhibitions - Fall 2004

|

Sexy Beasts: |

August 18 - October 13 |

Drawing the Line: |

September 30 - October 30 |

Captive Beauty: Zoo Portraits by Frank Noelker |

October 18 - December 11 |

Photographs by Ulli Beier |

| November 4 - December 11 |

|

| Sexy

Beasts: Prints by Lawrence Brose and Paintings by Michelle Dussault

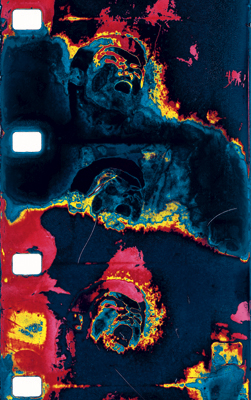

Lawrence Brose This exhibition of large-format Iris prints is drawn from a filmwork entitled De Profundis that, in the words of its maker, explores the “transgressive aesthetics of Oscar Wilde and contemporary queer culture.” In the film, footage from an early home movie depicts sexually ambiguous males who apply suntan lotion to each other on the deck of a pleasure boat, and is interfused with sailor-daydream pornography and sexually ecstatic faces surfacing in overlapped or duplicate motion. A creepy chorus intones certain aphorisms of Wilde’s (“The only way to rid of temptation is to yield to it”) in male voices sound-looped into timbres fiendish or demonized, effeminate or sissified—a veritable black mass of cathedral whispers and limp-wristed rapture performing the ambiguities that exist between the individually willed and the socially settled. Brose’s sexual politics are at the far end of any normative identity; his work embraces the deviant or embarrassing against the pathology of sameness as countered also by the radical, the outlandish, the transgendered, and the unwittingly homo. During these times troubled by the current state of the globe, where difference is gravely threatened by an anxiety manufactured in the name of an overarching national identity and the beckoning ideology to unite, these prints are a challenge for us to consider the repercussions of being socially marked and potentially targeted—hence vulnerable to profile and censure. It is the task of difference now to proliferate, both as represented in art or as braved in society, imperative still to render human relations complex and in creative collision with that impetus of the same whose sole imagination is to deem dangerous all things that lie beyond its claims on the visible. - from an essay by

Roberto Tejada

Michelle Dussault My envious disgust at pair bonds, as a lifestyle and a reproductive strategy, is an often-visited topic in my work. The search begins with an investigation of heterosexuality motivated from a presumptively homosexual lens. As a heterosexual woman raised by closeted homosexual parents, I have felt loosely associated with a kind of homo-mulatto-esque “race,” a concept somewhere between culture and biology that I would like to strip down and see lying naked on the floor. The ambiguous orientation of explicit imagery in my paintings suggests an unorthodox position and tells a slightly different story, one in which heterosexuality is as strange a concept as it was for me growing up in a homosexual matrix. Sex was never meant to be part of the equation. Reproduction was supposed to slip gracefully into representation without soiling the sheets. But there it was waiting to assert itself as part of the process or part of the problem, waiting to complete the formula, to bring the numbers together, or to keep them apart. 23+23=__. I haven't forgotten the lesbian or gay couple. Tic. Or the uncertain reproductive options of the single, toc, the barren, the infertile, the impotent, or the ugly. Tic Toc. There are always arrangements that can be made: back doors in and out of, ways around biology, beneath or on top of it, outside of or curled beside its suggested methodology. But they’re not always the way I like it, fast and cheap. Tic Toc. - MD Drawing the Line:

The images selected for this show remind us of the broad scope of the cartoonist’s imagination, which finds its subjects in the rarified air of world politics as well as in the mundane arena of daily life. Styles, too, run a gamut, from melodrama to soap opera, from whimsy to satire. Today’s editorial cartoon, with its sardonic take on the doings of the great and not-so-great, would have seemed familiar to 18th-century readers, who were used to seeing their leaders mercilessly lampooned. Tom Tomorrow’s comic portrait of Clinton as a lava lamp and Shoemaker’s rendering of Nixon’s attempt to coax a wallflower Ho Chi Minh into a peace tango are thus part of a long tradition of visual satire. In Garry Trudeau’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Doonesbury series, we see the lampoon tradition married to what was essentially a 20th-century development—the comic strip. The strips gained their initial momentum on the battlegrounds of the newspaper circulation wars, which were often fought on the colorful pages of the Sunday supplements. It was here that the basic characteristics of the strip were established. In the pages that entertained readers with the adventures of Buster Brown, Little Nemo and Krazy Kat, most of the familiar techniques came to maturity. Sequentially arranged panels depicted the humorous doings of a recognizable cast of characters, using a highly integrated combination of images, words and graphic conventions. When artists and writers began to team up in the 1920s to create the lengthy narratives of the so-called continuity strip, the genre was more or less complete. Social historians will find much of note here—for example, the way gender roles are uncritically reinforced in these predominantly 1960s images. It is only in the more recent work of Inuit artist Alootook Ipellie that we see issues of ethnic identity addressed head-on. So here in the deft curve of a line and the sinister play of a shadow, in one fell stroke, or in the slow unfolding of a multi-character narrative, our foibles, our fears, our fantasies, and our passing fancies are laid out for inspection. In these images, too, the past and the future of the mass-circulation comic arts are on display in all their rich variety. Included in the exhibition:

Card text by Kerry Grant, professor and chair of the English department at St. Lawrence University. Many of the cartoons in the exhibition were donated by Publishers-Hall Syndicate in 1969.

Frank Noelker’s work makes a powerful statement.

It is both beautiful and profoundly disturbing. He has captured,

in this series of portraits, the very essence of the problem of

zoos. For here we see “wild” animals who are no longer

wild. In some instances the walls of their cages have been skillfully

painted so that, at a quick glance, they appear to be large, spacious

enclosures—in their natural habitat, almost. Yet the artwork,

the painted trees and vines and flowers, serves only to render

more heartbreaking their stark imprisonment. To collect the images, Frank toured zoos in many parts of the world and spent days sitting, watching, and waiting for the shot that would convey the story of captive lives, the indomitable animal spirits that refused to give up, clinging to the last vestiges of freedom within their hearts. Frank’s heart was broken again and again. And I understand, for I too have looked into the eyes of three-hundred-pound gorillas destined to spend the rest of their lives in small enclosures while human animals gather to stare and point. And there are other eyes that haunt me: the eyes of elephants chained to the ground, of wolves, those wild, free spirits of the north, in small pens reeking of urine, and worst of all, the eyes of dolphins taken from the deeps of their ocean world to swim round and round and round and leap out of the water to catch plastic balls. Let us hope that the day will come when the steel-barred cage, the concrete island, and bare, sterile enclosures of all sorts will be no more. Frank’s work, with its implicit plea for our sympathy and understanding, will play a part in making this happen. Jane Goodall

Mbari Houses: Photographs by Ulli Beier

The custom of building mbari houses, monuments honoring Ala, the Igbo creator goddess, is limited to a region in Nigeria around the town of Owerri. Mbari are unfired, painted mud figures constructed by young boys and girls from a certain age group who work under the supervision of senior craftsmen. The artists, working from nine months to a year, live in total seclusion outside the village on a piece of land that has been fenced in with palm leaves. A mbari house is not a shrine. After a sacrifice is brought to Ala, no further ceremonies take place there. Exposed to wind and rain, the figures crumble within a few years, and then the next age group will construct new mbari. Some key figures must be represented in these monuments: Ala, the earth goddess with a child sitting on her lap, typically wields a sword in her right hand; her consort, Amadi Oha, the god of thunder, is often dressed in a topee and tie like a British district officer; and various river goddesses serve to affirm the cycles of nature. Young artists invent other gods, people, and animals: Christ in a schoolboy’s uniform, a schoolteacher with a book, a tailor with a sewing machine, women in childbirth, gorillas, monkeys, dogs, horses, leopards, and horned fantasy creatures called “elephants.” The ephemeral quality of mbari is essential to its meaning and purpose. It would have been easy enough for the builders to protect the figures from wind and rain, or the artists could construct heavy, solid forms with arms closely attached to the body, like the mud figures found in Benin City in shrines dedicated to Olokun, the god of the sea. However, mbari artists seem to provoke decay by representing Ala with an outstretched arm, or portraying a leopard pouncing onto a goat. In the mbari tradition, the act of creation is more important than the finished object. The function of the building is to honor the goddess of creation and thereby ensure the productivity of the earth and the survival of the community. The very short life span of mbari houses allows every age group in the village to participate in this eternal cycle. -Ulli Beier

Der Drache, die Jungfrau,

und die Tribune/ The Dragon, the Virgin, and the Grandstand:

An Installation by

Suse Weber und/and

In contemporary Germany, Übergangsgeneration is a colloquial term that refers to the transitional generation of east Germans who came of age in the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR) prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Suse Weber was born in 1970 in Leipzig, the city described as the epicenter of the “peaceful revolution” of 1989. Jan Bleicher was born in 1966 in East Berlin, the capital of the former GDR. Like others from this generation, Weber and Bleicher learned professions in the east and, when the Wall came down, were forced to re-orient themselves to radically changed circumstances. Neither Weber, trained as a kindergarten teacher, nor Bleicher, trained as a plumber, has held a permanent position in those professions. Since 1990, Weber has moved through a series of off-the-books, part-time jobs, including construction, art installation, and shoe sales, while Bleicher usually works in construction as a manual laborer. Today, most east Germans remain economically and socially marginalized. Despite massive investment and the rapid transfer of west German political, economic, and cultural structures into the east, the region’s unemployment rate hovers at 20%.

It is under these difficult circumstances that Weber and Bleicher create their art. Each responds differently to the disappearance of the nation in which they were born and the more recent commodification of life under capitalism. Whereas Weber’s installations examine the memory of and nostalgia for life in the GDR, using artifacts such as military uniforms, household products, and national symbols, Bleicher’s photographs make no direct reference to the past and instead depict contemporary urban buildings and parks usually devoid of people. Weber’s installation, The Dragon, the Virgin, and the Grandstand, draws together elements of fantasy, folklore, commerce, and sport. Structured to resemble a grandstand or medals podium in a sports stadium, the installation critiques the use of sports spectacle in the service of nation-building, whether communist (as in the case of the former GDR) or capitalist (as in the case of the United States, especially during a year which includes both the Olympic Games and a presidential campaign). On the other hand, in Stroll, Bleicher observes the world from the point of view that might be described as that of a stray dog wandering through a park. On view are images of thick, lush shrubbery in its deep stillness, vacant architectural structures, or anonymous tourists equipped with cameras of their own. -Joel Morton

Gallery Hours All exhibitions and related educational programs are free and open to the public. The Gallery welcomes individuals and groups for guided tours; please call (315) 229-5174 for information. The Gallery will be closed November 20-29 for Thanksgiving break.

|

| top of page |