Exhibitions - Spring 2005

|

Histories

Are Mirrors/The Path of Conflict through Afghanistan and Iraq: |

|

|

|

Chenrezig

Buddha of Compassion |

January 17 - February 19 |

Permanent/Temporary: Sharpie Drawings and Prints by Alicia Giuliani |

February 28 - April 2 |

Incongruent: Contemporary

Art from South Korea |

|

Annual Barnes Endowment Juried Student Art Exhibition |

| April 13 - June 6 |

Common Threads: Textile Production

in India |

| Histories

Are Mirrors/The Path of Conflict through Afghanistan and Iraq: Photographs by Tyler Hicks

Northern Alliance soldiers face the onset of winter at the mountainous front-line in the Hindu Kush. The Salang Pass is about sixty miles north of Kabul, less than a mile to the Taliban forces. Before 9/11, I had never photographed an American war of the magnitude we’ve seen in Afghanistan and Iraq. The conflicts I had covered were other people’s wars, far from home, in unfamiliar cultures and countries. Although it was the United States that bombed the Milosevic regime, where we photographed the peacekeeping mission that followed into Kosovo, the stakes there were ultimately European. Afghanistan and Iraq were about us, and I can’t pretend the stakes didn’t matter to me. Emotions were higher and more immediate, and the pictures and stories that came out of the war reflect that feeling…. … It is the tendency of every nation to cast its wars in terms of good and evil, and the war in Afghanistan was no different. Our side, the white hats, won, but this only demonstrated the complications of victory. I was traveling with one of the first groups of Northern Alliance soldiers to reclaim Kabul from the Taliban, when the soldiers captured a wounded Taliban prisoner. Without remorse, with something strangely like joy, they quickly executed him before continuing their mission south. In that moment, the fact that they were soldiers did not seem relevant. I saw our shocking lack of humanity. They—like me, like the man they shot—were all human beings. Those who died and killed there did so, not because of their passion to fight, but because they had been ordered to. And the real enemies, the masterminds with bank accounts who put pen to paper, the men who had started the terror, some of those fled east to the tribal areas at the border of Pakistan or south to strongholds in Kandahar, while others were in Washington. I wondered who had been defeated and what the conflict had cost all those it touched. In the end, perhaps good and evil exist in constant, fluid exchange, running into each other as we move beneath the pressures of the world…. -TH

Marines

watch over Iraqi detainees gathered in Najaf following an early

morning raid on a former Iraqi police station in Kufa, a gathering

place for Mahdi militiamen loyal to radical cleric Moktada

al-Sadr. Some of the twenty-nine captives claimed that they

had been held hostage because they wouldn 't cooperate with

the militia and were turned over the Iraqi authorities for

further questioning.

Tyler Hicks was born in São Paulo, Brazil, in 1969 and graduated with a degree in journalism from Boston University in 1992. After working for a number of years as a news photographer, he traveled to Kosovo in 1999 and Kenya in 2000-2001 on contract for The New York Times. Hicks traveled to Afghanistan after 9/11 to document the war against the Taliban for The Times and Getty Images. The recipient of the 2001 International Center for Photography Infinity Award for Photojournalism for his coverage in Afghanistan, he has also received awards for World Press and Pictures of the Year. As a Times staff photographer since 2002, Hicks has traveled to Iraq on several occasions to document the ongoing conflict. Histories Are Mirrors is a traveling exhibition organized and circulated by Umbrage Editions (see www.umbragebooks.com for more information). Special thanks to Nan Richardson, curator, and Launa Beuhler, director of exhibitions. GET YOUR WAR ON:

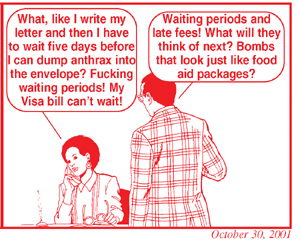

…[The] confusion is all there in the debut of David Rees’s Get Your War On, in the October 9 edition that started the strip. From panel to panel, our clip art cousins and doppelgängers veer from wrath to self-loathing, ricochet from manic jingoism to giddy despair. They get high on the idea of carnage and then get down with the whiskey in the bottom drawer of their desks. Whether describing the comic or tragic, their expressions never change. They learn nothing from one installment to the next—in fact, [they] only wade deeper into the morass of absurdity, lured in by the latest catastrophic news report. Frozen in ignorance. Paralyzed by helplessness. Of course, Rees’s characters are more than cookie-cutter people uttering cookie-cutter phrases: they are numb like us. The first strip in Get Your War On is a transcription of a conversation Rees had with a friend. Along with many of their neighbors, Rees and his pal had retreated into language. Relief Effort, Heightened Awareness, Enduring Freedom—these were the syllables we used to keep the world at bay. Like George Carlin with a modem, David Rees has a knack for pointing out how we abuse words, distort and torture them toward petty ends. The slang of hip-hop kids strides forth through television and radio, the bloodless inanities of politics trickle down through teleprompters and talking heads, and this sentence is born: “Operation: Enduring Freedom is in the house!” And this sentence makes sense to us, we recognize this monstrosity as our own. Rec room, board room, war room, news room—it does not matter, they all rely on the same useless phrases. What we see and appreciate in Get Your War On is David Rees’s attempt to make the words work again—to make us accountable for our avoidances, our ellipses. As the link to his Web site was passed on, e-mail by e-mail, his comics reinvigorated the community. We had been atomized by television, separated from each other. Isolated first by images of horror, then brainwashed by the latest code words for brutality, banality, and other sorts of human nonsense. Forward this link, pass on this message. It will make you smile. Shit is pretty fucked up at the moment, the e-mails said, but at least we are not alone. It’s called comfort. Take it where you can get it. -Colson

Whitehead

A display of seven prints by David Rees from Get Your War On will be presented in the gallery from January 17 through February 19, 2005, in conjunction with the exhibition Histories Are Mirrors: The Path of Conflict through Afghanistan and Iraq by photojournalist Tyler Hicks. It is estimated that up to 300 people are injured or killed by landmines in Afghanistan every month—the highest rate in the world. More than 800 square kilometers of residential area, commercial land, roads, irrigation systems, and primary production land are littered with mines and unexploded ordnance. All of the royalties from Get Your War On (Soft Skull Press, 2002) and Get Your War On II (Riverhead Books, 2004) help support the Mine Detection & Dog Center Team #5 as they continue to work on clearance projects in western Afghanistan in the first and vital steps towards reconstruction. See www.mnftiu.cc for more information. David Rees is also the author of My New Fighting Technique Is Unstoppable (Riverhead Books, 2003) and My New Filing Technique Is Unstoppable (Riverhead Books, 2004). Special thanks to the Carlyle and Betty Barnes Endowment Fund. Chenrezig Buddha of

Compassion

From Friday through Sunday, January 21-23, 2005, the Venerable Tenzin Yignyen will construct a Tibetan Buddhist sand mandala at the Richard F. Brush Art Gallery at St. Lawrence University. He will also present a “Teaching and Meditation on Compassion” in the Gallery on Saturday, January 22 at 7:30 p.m. For three weeks in the spring of 1999, Tenzin constructed an elaborate Kalachakra Mind mandala at St. Lawrence University. This year, for three days only, he will construct a Chenrezig mandala based on the Tibetan Buddhist deity of compassion. Also known in Sanskrit as Avalokiteshvara, Chenrezig is the manifestation of the infinite compassion of all Buddhas. His Holiness the Dalai Lama is understood to be the living incarnation of this deity. A sand mandala is a complex, symbolic representation of the cosmos and is used as a tool in meditation and visualization in order to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. According to Sidney Piburn and Tenzin Yignyen, “each mandala is a sacred mansion, the home of a particular deity who represents and embodies enlightened qualities such as wisdom or compassion. Both the deity, who resides at the center of the mandala, and the mandala itself are recognized as pure expressions of a Buddha’s fully enlightened mind.” Matthieu Ricard, a Tibetan Buddhist monk and scholar, writes that mandalas “transform our ordinary perception of the world into a pure perception of the Buddha-nature which permeates all phenomena. Compassion is born from the realization that both the individual ‘self’ and the appearances of the phenomenal world are devoid of any intrinsic reality. To misconstrue the infinite display of illusory appearances as permanent entities is ignorance, which results in suffering. An enlightened being—that is, one who has understood the ultimate nature of all things—naturally feels boundless compassion for those who, under the spell of ignorance, are wandering and suffering in samsara [the endless cycle of existence]. From similar compassion, one does not aim for one’s own liberation alone, but vows to attain Buddha-hood in order to gain the capacity to free all sentient beings from the suffering inherent in samsara.”

Tenzin Yignyen was born in Phari, Tibet, in 1953. He is an ordained Tibetan Buddhist monk who received a Master of Sutra and Tantra Studies in 1985 from the Namgyal Monastery of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India. After two years in Mongolia in 1993-94, Tenzin taught Tibetan Buddhism, sacred and ritual arts, and language at the Namgyal branch monastery in Ithaca, New York. He has since created sand mandalas in museums and educational institutions throughout the United States, including the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, the Rochester Memorial Art Gallery, and the Asia Society in New York City. Tenzin is currently a visiting professor of Tibetan Buddhist art and philosophy at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York. These Tibetan Buddhist programs are co-sponsored by the University Chaplain’s office as part of a “Fortnight of Non-Violent Events” from January 17 (the commemoration of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday) through January 30 (the anniversary of Gandhi’s assassination and the date of the upcoming elections in Iraq). During this two-week period, a series of lectures, films, discussions, and other activities are scheduled to highlight nonviolent ideas and actions from a variety of disciplines and faiths. At 10:00 a.m. on Friday, February 18, 2005, Tenzin will conduct a dismantling ceremony which will be followed by a walk to the river. For more information, please contact Cathy Tedford, Gallery Director, at 315 229-5174. “The mandala is dismantled in order to demonstrate the truth of impermanence and so that the sand, which as been made sacred, might be distributed to onlookers and put into the environment (typically, a body of moving water) as a blessing. The monks lead a procession, which may be a pond or lake, but in order that the blessing of the sand extend as far as possible, the ocean, or a river leading to the ocean. The monks ask the protective spirits of the water to accept the blessed sand and to protect the inhabitants of the local environment.” -Daniel Cozort, The Sand Mandala of Vajrabhairava

Upon graduation from St. Lawrence University in 2004 with a degree in fine arts, Alicia Giuliani is the program director at the Adirondack Lakes Center for the Arts in Blue Mountain Lake, New York, where she organizes rotating exhibitions, concerts, and other events and activities. As a student, Alicia approached most every task or project, even the most unlikely Web site (“I LOVE www.orangecountychoppers.com!”), on a continuum somewhere between enthusiastic and obsessive, documenting, for example, in all her favorite Sharpie colors—pinks, reds, black—each of the 24 hours of her recent 21st birthday, as well as a whirlwind trip to New York City (highlighted by a “really good” honey chicken dinner at Applebee’s in Times Square) to return a Tibetan Buddhist monk to his brother. One late winter night, the three of us spent a few hours googlewhacking, playing a variation of the online game where we entered three disparate terms on the search engine in order to come up with results that “did not match any documents” (einstein-cattywampus-google; hefner-eyelash-hepatic; and endometriosis-heinous-mandala). It’s harder (or easier?) than you think. “Curious,” Alicia would say, like an all-knowing Cheshire cat. Her most recent work depicts icons of girlish femininity: tiaras, diamond rings, a princess in a burning castle, flippy evening dresses and fancy shoes, bras and underwear—images (and content) she culls from the unreality of women’s fashion magazines. Her process is fast and sure; she doesn’t waver in this weird juxtaposition of aggressive girlie-ness. Yet despite her unflinching self-assurance and feisty self-awareness, Alicia explores deeply personal issues in her life with humor and humility. -Cathy Tedford and Carole Mathey

“What I’m interested in at the time is what my work is about” is a comment I wrote in my journal last spring that applies to my recent drawings and prints. The work in this exhibition is comparable to a visual journal, inspired by and made for specific people in my life, in which I challenge the probability of normalcy in personal relationships. I attempt to fabricate tangible statements and, through the use of layering and multiples, form more nuanced meanings. A monochromatic palette is vital, and I use the color pink specifically to suggest notions of happiness, delight, love and passion. Upon closer inspection, however, the color pink can also elicit feelings of annoyance, confusion, humiliation, resentment, anger, jealousy, or even aggression, and I like seeing seemingly innocent subjects turn malicious. I use Sharpies exclusively because they are so consistent, allowing me to create the same types of marks throughout a body of work. They can also be used on a wide range of materials such as packing tape, bubble wrap, metal, Plexi, and mirrors.

Incongruent brings together nine artists from South Korea, with the exception of Yong Soon Min, a Korean-American artist based in Los Angeles. The participants include two artists closely associated with Min Joong (people’s art), a cultural and political movement of the 1980s. They are juxtaposed with five younger artists who work in conceptual and performance-based photography, videos and Web-based projects. The link between the generations lies in the artists’ investigations of the visible and pervasive forces of modernity in Korea and in their critical reception of western cultures, as they examine the presence of the United States and scrutinize the division of the Korean peninsula. The works in this exhibition present South Korea’s hybrid material culture as a direct result of international politics related to the Cold War and globalization, or more appropriately, what is known as glocalization. In terms of strategy, the artists share an understanding of the importance of everyday experience and conceptual apparatus beyond the studio. For example, Kim Yong-tae’s photographs of U.S. soldiers and their Korean spouses were found in commercial photo salons near the U.S. Army base in Seoul. Kim’s rearrangement of the photographs reveals how they operate on a personal level based on the concrete pursuit of happiness, just as they testify to the power dynamics between two nations and their peoples, and how the complex is often situated in the mundane. Through his paintings Spring Rain Descending a Staircase and Mondrian Hotel, Joo Jae-hwan criticizes the tendency among South Korean artists to imitate western modernism. Deviant yet aligned with the iconoclastic gestures of Duchamp and Warhol, Joo’s work parodies a South Korean social hierarchy determined by military power, material wealth and elitism. Just as the work of these senior artists is subversive in nature, there is also something oddly incongruent in the other artists’ work. Koh Seung-wook’s performance-based photographic project is an absurd, ephemeral, seemingly insignificant happening, but it addresses the fundamental nature and values of artistic activity and industrial production. In his series Playing in the Vacant Lot, Koh digs a hole in frozen ground and plays naked in it, sometimes with a swimming tube, other times drinking alcohol. He appears at odds with the Korean national fervor to work hard, produce and achieve in a never-ending struggle for economic prosperity. Koh’s performance is not a reflection of hedonism; rather, his mundane routine is actively anti-art and anti-commodity. In an empty piece of land sitting idle, his intervention questions the global frenzy of economic development. Among the participants, Yong Soon Min is the only artist who can legally travel to North Korea. In her video projection, she portrays North Korean women dancing to celebrate the “victory” of the re-election of Kim Jung-Il to the parliament. They are superimposed onto the portraits of die-hard communists appropriated from North Korean stamps, individuals who were imprisoned in South Korea for their refusal to renounce their loyalty to the North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung. The joyous movement of the dancers evokes a funereal commemoration of these victims of ideologies.

Jo Seub, through his re-enactment of violence and repressed adolescent sexuality, interrogates the uncomfortable collective memory of his generation who grew up during the oppressive military regime endorsed by the United States. Yoon Joo-kyung makes a futile attempt to claim the Wild West by holding a red flag at Monument Valley, Arizona, the backdrop of John Ford’s movies. Kim Sang-gil presents images that are simultaneously calm and confident, yet sharply disturbing. In one picture, a man talks on his cellular phone at a traditional gazebo in Seoul, precariously balanced atop a rocky hill with a vast view of the urban landscape. Other images reveal private Internet communities who gather to flaunt their Harley Davidsons, Burberry dresses, and mobile homes.

In his video Power Passage, Park Chan-kyong investigates the disparity in the power and ideology during the Cold War era by juxtaposing the much-publicized, spectacular linkup of the U.S. Apollo and the Soviet Soyuz spacecrafts in 1975, along with North Korea’s underground tunnel across the DMZ to invade South Korea. Finally, in his Web-based projects, Roh Jae Oon demonstrates the notion of incongruency through the dissonance between narrative voice-over and image, as well as the disjunction between what is addressed and what is implied. In Three Open Up, for example, the voice narrative describes a South Korean delegation’s tour of North Korean pig farms, while shots from U.S. satellites reveal North Korean nuclear weapons construction and launching sites. -Young Min Moon Special thanks to a grant from

the Freeman Foundation to St. Lawrence University’s Asian

Studies Initiative and to the Jeanne Scribner Cashin Endowment

for Fine Arts.

Barnes Endowment Annual Juried

All St. Lawrence students are eligible to enter up to four works of art in any media on Tuesday, April 5 from noon to 5:00 p.m. and on Wednesday, April 6 from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The exhibition will open on Wednesday, April 13 at 7:00 p.m. featuring live music with Blue Clover. Please join us! The exhibition is juried by Ana Rewakowicz, a Montreal-based artist and researcher who works with inflatables and explores relations between temporal, portable architecture, the body, and the environment. The exhibition is supported by the Carlyle and Betty Barnes Endowment and the Jeanne Scribner Cashin Endowment for Fine Arts. Common Threads: Textile Production in India

During the fall of 2004, I traveled by bus, train, moped, horse, bicycle, camel, elephant and rickshaw across India to conduct a photo documentary research project on textile production. From the glacial source of the Ganges River in the Himalayas to Muslim neighborhoods in Varanasi and commercial districts in Jaipur in the middle of the desert near the border of Pakistan, I photographed textile workers in rug factories, cotton mills, power loom production sites and private homes. I was conscious to photograph people at their own physical level, often sitting on the floor right next to them in order to avoid creating images that would present any perception of superiority on my part. I also found it ironic that in a country radiating with sunlight, I typically photographed in dark, cramped spaces using minimal natural light.

Gallery Hours All exhibitions and related educational programs are free and open to the public. The Gallery welcomes individuals and groups for guided tours; please call (315) 229-5174 for information.

|

| top of page |