Exhibitions - Spring 2004

|

|

January 19 - February 21 |

|

February 26 - April 3 |

Visual Prayers: Sacred Tibetan Buddhist Thangka Paintings |

February 26 - April 3 |

Photographs by Matthieu Ricard |

April 13 - June 7 |

Prints by Eric Avery |

April 13 - |

|

April 13 - |

|

April 13 - |

|

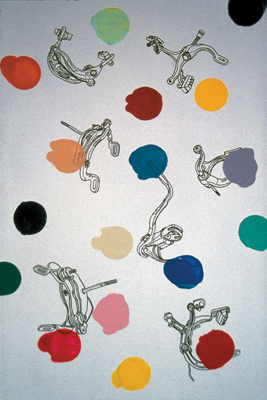

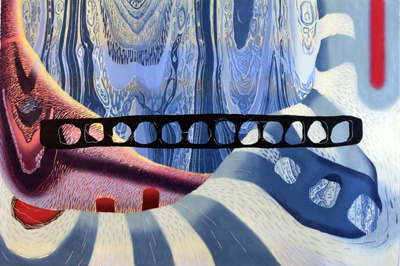

| LOST/FOUND Young Min Moon Melissa Schulenberg

My work addresses the powerlessness of the immobile and voiceless. Paintings in the recent series Immobile Parts for Sale are littered with unwanted bicycle parts, which are no longer capable of producing desired speed or power, yet celebrated by cheerful color spots and other formal arrangements. Objects meander and float about, as the paint is applied freely, suggestive of motion, speed, and controlled chance elements. The images are potentially erotic as well. Tensions between belief and doubt are highlighted as I seek to corrupt the legacy of purity in abstraction. The representation of hands signing in the series Against Homogenizing Impulses addresses the ambivalent relationship maintained by a minority to any “official” language, artistic or otherwise. While seemingly playful and joyful at the surface, my paintings convey subtle political messages without relinquishing visual pleasure. My work only appears to belong to “mainstream” art, yet it is not easily categorized as art of the “Other.” Recently, I have utilized aleatory elements, including color samples of paint from Home Depot and images culled from illustrators’ idiom dictionaries. These predetermined elements are juxtaposed against my impulse to compose and order a wide spectrum of color and imagery. In short, my work is an aggregation of “hands-on” and “hands-off” as well as pure and impure elements of abstraction. - Young Min Moon

For the past decade, I have lived a nomadic life, crisscrossing my way around the country, a quiet observer of various landscapes and environments. Escaping to the mountains, coast, or prairie has provided a solitude that has kept me grounded and given me a sense of ownership in these temporary locales. I look for small treasures: thorns, bones, tufts of deer hair. Observations of these organic remnants lead to intimate visual explorations and formal abstractions—I examine a seed pod, draw it as simply as possible, then put it away. Everything else is a direct result of the drawing or printing process and my memory of specific locations. Ultimately, an object manifests itself into a new reality, different from its source, yet maintaining an essence of its origins. Viewers experience these compositions as examinations of small objects seen magnified or as microscopic details, as I confound micro- and macro-perspectives. Each work contains infinity; each contains its own time and space. - Melissa Schulenberg

Steven Benson, Qutang Gorge, Fengjie, 1999, gelatin silver print The Three Gorges Dam, 610 feet high and 1.3 miles wide, will create a reservoir on the Yangtze River fifty miles longer than Lake Michigan. As the largest concrete object on the planet, it will ultimately force more than two million people to vacate their homes and disrupt the lives of 30 million people who live in the region. The reservoir will flood 8,000 known archaeological sites; 250,000 acres of China's most fertile farmland; and 1,600 factories, many of which have been burying toxic materials in the ground for the past fifty years. Scientists fear that lead, mercury, arsenic and dozens of other substances, including radioactive waste, will leach into the river’s watershed. Dr. Sun Yat-sen, considered to be the father of the Chinese Republic, initially discussed the project in 1919 as part of his Plan for National Reconstruction. The dam was also of great interest to his successors, including Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek , as well as Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, though it never generated strong support. However, in the wake of the Tiananmen Square protest in 1989, the government needed to bolster national pride. The collapse of the Soviet Union was an additional motivating factor, and in 1992, Premier Li Peng, a Russian-trained hydro-engineer, pushed the project through the National People’s Congress; one-third of the delegates voted against the dam or abstained. Construction began in 1994. The Chinese government cites three principal reasons to build the dam: to generate 11% of the country’s electricity (the equivalent of 18 nuclear power plants), reducing its need for coal-burning facilities; to control the Yangtze’s devastating annual floods which have claimed the lives of more than 300,000 people during the last century; and to improve the standard of living in one of the most impoverished parts of the country by allowing 10,000-ton ships to move goods in and out of the heart of China. As part of a 14-hour television broadcast celebrating the blocking of the Yangtze on November 8, 1997, President Jiang Zemin noted, “This proves vividly once again that Socialism is superior in being capable of concentrating resources to do big jobs. Since the twilight of history, the Chinese nation has been engaged in the great feat of conquering, developing, and exploiting nature.” On June 10, 2003 at 10:00 p.m., the reservoir began to fill, reaching a depth of 425 feet in spite of the 100 cracks that were discovered in 1999 running the full height of the upstream face of the dam. The cracks were repaired, only to reopen. Chinese engineers claim this is common, but others suggest it is due to the improper curing of concrete. In 2009, the reservoir is expected to reach 575 feet, completing the flooding of 13 cities, 140 towns, and 1,352 villages. - Steven Benson

For more information about the artists, see:

Visual Prayers

I awaken before dawn to the sound of monks chanting at the Shechen Monastery next door. By 8:00 a.m. I arrive at the Tsering Art School where I’ll be learning to draw and paint traditional Tibetan Buddhist thangkas. The tinkling of chimes, disharmonious to my ear, calls the students to gather. Everyone enters the room by prostrating three times in front of an altar with a poster of the Dalai Lama smiling down at us. Sitting in predetermined spots on the floor, fifty students sit side by side on cushions in a hot but airy room; the most advanced Tibetan and Nepalese students face the rest of us. I sit in the back row with others from Australia, the Philippines, Germany, and France. The teachers walk in last, and we stand to greet them. We pray for thirty minutes, reciting in Tibetan the Seven-Limb Prayer, the Lineage Prayer, and others. Dak sok drokun changchub partu lama choksum kiapsu nyen (I and all beings take refuge until enlightenment ). Each day is devoted to a different deity: Monday to Sakyamuni Buddha, Tuesday to Tara, Wednesday to Guru Rinpoche, etc. Two days a week, there are special dharma teachings in Tibetan. In the mornings, we draw freehand for two hours using sharpened bamboo sticks on wooden slates prepared with ghee and talc. The teacher draws a simple leaf in the corner of my slate, and I spend the next two classes trying to copy it exactly. No one is interested in my personal expression. After the teacher approves my work, I erase the whole thing with a rag and prepare the wooden slate again. Little is permanent in this endeavor. Two weeks pass, and I’m allowed to move up to a chrysanthemum blossom. I take pictures of my work to show my friends at home, and the other students laugh at this as they draw the graceful hands, feet and face of the Buddha. Some draw intricate, wrathful deities, spending close to a week on detailed renderings, erasing their work after the teacher permits. In the afternoons, we paint with watercolors. The teacher applies the pigment so delicately, brushing leaves and clouds with graceful strokes…. The intention to create or view a Tibetan Buddhist thangka painting is to “attain enlightenment for all sentient beings and to be able to change [our] minds to that of the Buddha’s mind or realm…[in order] to destroy…conflicting emotions.”1 The idea of painting as a spiritual or sacred act, an offering, had not occurred to me in this way before, having been trained to make and exhibit objects. Yet as visual prayers, thangkas function in terms of both product and process. As objects, they are used to visualize the energies of particular deities or to understand the nature of emptiness, for example. Likewise for the artist, the creation of a thangka is a meditative offering guided by pure intentions related to dharma teachings. - Cathy Tedford, Director 1David and Janice Jackson. Tibetan Thangka Painting, Methods and Materials. Ithaca, NY; Snow Lion Publications, 1984.

Thangkas from the Shelley and Donald Rubin Collection, the Rubin Museum of Art, and St. Lawrence University’s Permanent Collection are on display. In addition, Kalsang Tsering Sherpa, a monk from the Tsering Art School at the Shechen Institute of Traditional Tibetan Art, is in residence from March 1 through 12 to create a thangka painting.

Kalsang Tsering was born in Baudhanath, Kathmandu, in 1981 and was placed in the Shechen Monastery when he was eleven years old to begin monastic training. When Konchog Lhadrepa started to teach thangka painting there in 1996, Kalsang had finished his preliminary studies and was asked whether he would like to train in the ritual or philosophical colleges of the monastery, or in the art school. He said he would like to make art, and Shechen Rabjam Rinpoche agreed this would be best for him. Kalsang was the first student at the Tsering Art School and graduated in 2001. He now teaches there. Special thanks to Charlotte Davis, Vivian Kurz, and Lisa Arcomano. Journey to Enlightenment

For me, photography is a hymn to beauty. In 1967, I traveled to Darjeeling, India, and met my first spiritual teacher, Kangyur Rinpoche. After he died in 1975, I spent twelve years with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, the archetype of a spiritual teacher, someone whose inner journey led him to an extraordinary depth of knowledge and enabled him to be a fountain of loving kindness, wisdom, and compassion. Over the years, I have photographed teachers, hermits, and yogis who are living examples of what they teach. The messenger has become the message. What they show outwardly is who they are within, without contradictions. Their contentment is not due to mere pleasurable feelings but is an expression of a sense of serenity and fulfillment that arises from exceptionally healthy minds. According to Buddhist teachings, Buddha-nature is present in every living being, and the natural state of one’s mind, when not misconstrued under the power of negative thoughts, is perfection. Positive qualities, such as a good heart, are believed to reflect the true and basic fabric of human beings. Yet even in intense suffering there can be dignity; even in the face of persecution and destruction there can be hope. This is particularly true for Tibet and its people, who have succeeded in retaining their joy, inner strength, and confidence while being subjected to a human and cultural genocide. These photographs provide a glimpse of a Tibetan Buddhist teacher’s life and a unique culture that, despite the upheavals in its homeland, still survives. It is an amazing experience to be in many places in Tibet, in the presence of beings whose hearts are filled with altruism and wisdom, and to try to mingle your mind with their minds. The intense silence, the immensity of the landscape, the deep blue sky and crisp air are such that when you sit there, you want to remain in the limpid harmony between the environment and your own serene mind. So, portraits and landscapes can lead you from an understanding of outer beauty to the inner beauty of spiritual awakening and the boundless human qualities that accompany it, as the warmth and light of rays naturally accompany the sun. - MR

Matthieu Ricard, an internationally respected writer, translator, and photographer highly regarded for his scholarship and knowledge of Buddhism and Tibetan culture, has lived and worked in the Himalayan region for the last thirty years. Born in France in 1946, he grew up in the intellectual and artistic circles of Paris studying classical music, ornithology, and photography. After completing his doctoral thesis in 1972 in molecular biology at the renowned Institut Pasteur, Ricard decided to forsake his scientific career and concentrate on Tibetan Buddhist studies. He lived in the Himalayas with the greatest living teachers of that tradition and became the disciple and attendant of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of the most eminent Tibetan masters of the 20th century. Ricard, a Buddhist monk, resides at Shechen Monastery in Nepal. Since 1989, he has often accompanied His Holiness the Dalai Lama to France as his personal interpreter. For three decades, Ricard has photographed the spiritual masters, landscapes, and people of Tibet, Nepal, India, and Bhutan. He is the author and photographer of Journey to Enlightenment (Aperture, 1996; republished in 2001 as The Spirit of Tibet) and has collaborated with Olivier and Danielle Föllmi on Buddhist Himalayas (Abrams, 2002). Henri Cartier-Bresson said of his work, “Matthieu’s spiritual life and his camera are one, from which springs these images, fleeting and eternal.”

The photographs in this exhibition were loaned by Aperture Foundation, New York, and by the artist. Special thanks also to Vivian Kurz. Doctor's Cuts: Prints by Eric Avery

I first met Dr. Eric Avery through a letter from Somalia. He was working as a doctor in a refugee camp with thousands of human beings who were starving to death. A photograph in Life magazine shows Eric in the middle of the camp that stretched for miles, a figure at dusk holding up a tiny baby into the light, silhouetted by dusty tents. It was there that Eric started to make woodcuts—to record the terrible sights he had seen and, as his scalpel cut into the wood, as therapy. If you are fortunate enough to be a friend of Eric’s, you will receive woodcut cards of plants and birds, shells and trees, as purely and simply illustrated as engravings by the 19th-century British naturalist Thomas Bewick. That would be sufficient for most artists, but for Eric, harsh truth is as urgently beautiful. Eric uses science and art in tandem to heal. He transmutes the chaff of suffering into art. Eric always says “life before art” as he plunges into healing the victims of society wherever he finds them—in crack houses, on death row—refugees on the broken borders of life or death, the poor, the abandoned. They become alive in his art; their content creates his form. His work as an artist/psychiatrist treating patients with HIV has become a document of historical record and is as sophisticated and powerful as any Dürer woodcut. It is the antibody to our disease of distance. Dominant culture flattens all experience, rendering reality into irony. We no longer trust ourselves to experience life directly. Eric makes art in the tradition of reportage; there is a direct emotional involvement with his subjects, a witnessing that is devoid of sentiment. The humility of small woodcuts depicting faces of cherished patients, printed on paper that is made from hospital sheets or the clothing of AIDS orphans, subverts and unravels the dominant social ideology of power and superiority. -

Sue Coe, artist and author/illustrator

See www.docart.com for more information about the artist. Traveling the Body

Line to line connection striving for a direction The vision comes from an intuition The

highlights are the colors are the Sketch on the beach - KC

Peace Amidst the Roots of Turmoil

I was a visitor to a country of which I knew little, and at the same time, of which I knew a great deal. Dinner-table conversations with family had led to my longstanding interest in anything Armenian. Over time, I developed an understanding of a culture that had once flourished yet was close to extinction as a result of the first genocide of the 20th century. During the winter of 2004, I traveled to the capital city of Yerevan, as well as small towns and villages in the Ararat Valley and north to Lake Sevan. In this short time, I met mothers and grandmothers, cab drivers, bakers, deacons, priests, young soldiers, and many children who all seemed to share a common vision of a better future, continuously looking forward while never abandoning their past. For most Armenians, history is not a detached experience. It permeates the memories of those who have survived and is reinforced in the minds of younger generations by ongoing economic hardship and present-day border disputes. Despite this, Armenians are often bound by deep friendships, generous hospitality, and an enduring national pride that has served as the backbone of this nascent republic. - AM Aram Muksian was the recipient of a Sol Feinstone International Study Prize through the St. Lawrence University’s Center for International and Intercultural Studies.

Ruth Bagley-Ayres, Dale,

2004, Student artwork in all media, including drawing, painting, photography, sculpture, ceramics, and printmaking, will be presented in this exhibition organized by the Student Art Union and the Department of Fine Arts. The Annual Juried Student Art Exhibition is open to all St. Lawrence University students. The exhibition is juried by Fritz Westman, a mixed-media installation artist based in Boston, and supported by the Carlyle and Betty Barnes Endowment and the Jeanne Scribner Cashin Endowment for Fine Arts. Gallery Hours All exhibitions and related educational programs are free and open to the public. The Gallery welcomes individuals and groups for guided tours; please call (315) 229-5174 for information.

|

| top of page |