Exhibitions - Spring 2003

| Lines of Migration: Paintings by Kenwyn Crichlow and Obiora Udechukwu

The question about lines—lines of departure, lines of enclosure, lines of demarcation, lines of separation, and so on—is an important part of the process of [understanding] community, especially in the diaspora. We’ve grown up with maps that show a line coming from Africa to the Caribbean and then breaking up; that is the line that describes the diaspora. I also relate [the idea of line as metaphor] to the lines that root me personally to Trinidad and to the rest of the world. I remember being asked at one point about my descent, and I say, as I look at my own physiology and the physiology of my relatives, that we seem to resemble Yoruba people. I don’t know if I am Yoruba or Igbo, whichever continental African nation, because the line that joins me to that continent is somewhere, but it has been snipped off; that is an area of darkness. But there is a line that joins me to the Caribbean, which is becoming clearer as I grow older because I’m now able to more usefully piece together the narratives and the anecdotes that members of the previous generations have told me. To restructure the past, to look at the social and political evolution of society and see where my family was in the landscape, [allows me] to work out the line that joins me to Trinidad or to the southern Caribbean. When we talk about issues of diaspora, [we] return to issues of race, class, and identity, issues of sociology and heritage. But there are other important issues upon which these also reside, which have to do with the making of things, which is one of the ways in which we define ourselves. People in Trinidad of African descent make things—much of this making comes out of the ramagé process, which is a way of improvising, of getting in touch with other areas of knowledge through time. My way of making a painting is informed by the ramagé process, which is part of the whole way of identification. I am informed by the discourse about identities. That is, I suppose, quite subjective, and maybe I am unable to tease it apart. It’s a value of negotiation, especially of identity. -KC

Obiora Udechukwu Although I have my Nigerian heritage, I’ve been living in the United States for five years, and you can’t exist as an island here. You have to be part of the society where you live; all kinds of things impinge on your life. How do you rationalize these things; how do you come to terms with your present position? There’s a lot of ambivalence in my practice now as an artist. In the 1970s, I moved away from strictly realistic painting and began to work in the Uli idiom. Typically, Uli painting by rural women in southeastern Nigeria is completely abstract and has a hard-edge effect. The colors are very few and not intermixed. Occasionally, I include figures in my work. For example, in a painting from the Dark Days series, people are huddled inside a cell. Although the picture references a specific and tragic period in the history of Nigeria, it transcends that. The work looks back several centuries to the infamous Middle Passage in which millions of Africans were transported in unspeakable conditions from the continent to the Caribbean and the United States to work as slaves on plantations. In the 1990s, the military government in Nigeria treated people in much the same way, locking large numbers of citizens in overcrowded cells without trial. At a personal level, I was incarcerated by the Nigerian military government in 1997 for some weeks, along with other academic colleagues. So, there is a link. I take the particular and use it to address the general. As far as I am concerned, human beings have not changed. Human beings have not changed at all. It is important for people in the diaspora to retain the good part of their culture. I say this because there is a tendency for people to give up everything they have when they encounter a “superior” culture. Look at the United States—so powerful; with its technological advantages it can take over any country, and so on. U.S. culture becomes the index, but it does not necessarily mean it is the best. Hillary Rodham Clinton wrote a book entitled It Takes a Village [to bring up a child]—and that’s the way we do it back home. Human beings are more important than capital. They are more important than money. The point I’m making is that it’s necessary for those of us who are in the diaspora to make sure that our children know our stories, our histories. -OU In May-June of 2002, in conjunction with the planning for this exhibition project, I attended part of a two-week summer institute at the University of West Indies for students from St. Lawrence University, Trent University, and UWI. Two concurrent seminars were offered: “cultural performance: arts and identity” and “social justice and comparative multiculturalism.” Among many other topics, we discussed the functions of carnival and the commodification of culture, and we learned about the history and politics of cricket in the Caribbean (and sat through most of a monsoon-like downpour to watch T&T fave Brian Lara in a match against India). I drove through Port of Spain with Ken Crichlow to find a gargantuan Spider Man billboard cutout perched atop one of Trinidad’s ubiquitous Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurants, right across the street from a monument to Captain Arthur Andrew Cipriani, an important activist in the country’s labour movement. One evening, students in the arts course performed in a cabaret of sorts, and I was stunned by their creativity and passion. I listened to a Celtic fiddler and a folk guitarist who sang Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up in Blue.” A storyteller shared a parable about the sun and the moon, and a visual artist/poet performed a radical feminist manifesto. On the BWIA trip home, “Shallow Hal” was featured as the “in-flight entertainment,” and I stopped off at the “America!” store in the Washington Dulles airport terminal to purchase Osama bin Laden “Terrorist” ID cards. As I tried to sort through this weird collage of images and phenomena, I realized that many of the concepts that the students explored in the institute were made evident in my travels. Lines of migration—people, capital, and cultures moving across borders, in ways that don’t often make sense. In this exhibition, Kenwyn Crichlow and Obiora Udechukwu reflect and comment upon issues of the diaspora and identity in the Caribbean and North America. As such, they are both eloquent narrators. Their work strives to make meaning of their own personal histories as well as the ambiguities and contradictions of contemporary culture. The juxtapositions reveal many lines of departure. -Cathy Tedford, Director

In January 2000, the Ford Foundation awarded St. Lawrence University a three-year faculty and curriculum development grant entitled “Crossing Borders: Revitalizing Area Studies” to work collaboratively with Trent University in Canada and the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago. Through the project, faculty and students at the three institutions have studied the relationships between geographic areas and the global movement of people, capital, and cultures across geographic borders, and they have investigated and compared the influence of Africa, Asia, Europe, and indigenous peoples within the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean from transnational, multicultural, and interdisciplinary perspectives. This exhibition was proposed by Eve Stoddard and Grant Cornwell, grant project coordinators at St. Lawrence, both of whom have long recognized that gallery programs can be well integrated into the academic life of an undergraduate liberal arts institution. Presented during the 2003 Festival of the Arts The Gullah Connection: From West Africa to the Islands of the Americas, the exhibition and educational programs are funded by the Ford Foundation grant. Special thanks to Carole Mathey at St. Lawrence University, Ronald Joseph at Gallery 1.2.3.4., and David LaRiviere at artspace for their assistance with the traveling exhibition.

Zalmaï Ahad,Niafounke, Mali, 1994,gelatin silver print I HAVE SORE EYES I had to leave without it. It was a Zenit, a Soviet camera my father had brought back from a trip. A crazy luxury for a child of Kabul who dreamed only of living in images. I was sixteen years old and had to flee Afghanistan like a thief. Months of travel followed. An itinerary without images, a black hole. I needed a reason to escape, and chance encounters gave it to me. The discovery of the world through photography showed me that my bewildered gaze was no longer alone. I had to set off again. But where? The question was rhetorical: where the dead speak nonsense, where misery spreads on beaches of silence. Wherever life overflows on itself, raw and naked. In Manila, on the steaming mountains of rubbish or in the swamps surrounding the shantytowns; in a camp of refugees, lost in Central Africa, where children dance under the stars; among nomads of every race, of every ethnicity. What does humanity have to say to these barefoot nobles, wounded to the bone, so close to lives nearly extinct, yet still burning brightly. Faced with these conflicting interpretations, I rage, I exult, and have the wild desire to open the eyes of those who have seen nothing. What use is photography? On the road fleeing Kabul, I remember a sea of white flags floating on a village turned graveyard. I do not know why I have kept this image, so sharp, of such aberrant disaster. In whose name? For what end? But it resonates in my eye like a reminder of reality. -ZALMAÏ Zalmaï’s photographs capture the slow, distressing drift of exile and dispossession: spectral figures against a stormy sky, a sheared row of peaks that frame a figure like a sacred relic, horizons of men, both of this world and of some timeless land. This is a documentation of a journey through ambiguous territories—from Cuba to India, Mali to the Philippines, Indonesia to Egypt, and a return to Zalmaï’s native Afghanistan—a search for place when one’s own land has been destroyed. Most of all, his work is about the fragility of presence. Born in Kabul, Afghanistan, in 1964, Zalmaï fled his homeland in 1980 to escape the occupation of the Soviet Army. He [moved to] Switzerland, where he studied at the School of Creative Photography, Lausanne, and at the Center of Professional Education in Photography, Yverdon. Since 1989, Zalmaï has worked as a freelance photographer for The New York Times, Le Temps, Geo, Newsweek, Reflex Magazine, Outside Magazine, and Vanity Fair. His assignments have taken him around the world, and his work has covered a variety of topics, from Tibetan refugees and rickshaw drivers in Calcutta to pygmies and Sudanese refugees in the Central African Republic, before bringing him back to his native Afghanistan to photograph the effects of landmines. Since his first solo show at 16/25 Gallery, Lausanne, he has had numerous others at museums and galleries throughout Europe. More recently, Zalmaï’s exhibition Afghanistan, produced by the International Red Cross, toured Switzerland, Germany, and Austria. He currently resides in New York City. On January 28–31, 2003, St. Lawrence University will host a peace conference entitled “The Real Situation: A Peaceful Anti-War Uproar.” Organized by Erin Cianchette ’03 and a committee of students and faculty, the event will bring together international and local scholars, activists, and musicians in an effort to shed critical light on a range of issues related to the ongoing “war on terrorism.” All of the events are free and open to the public; see http://student.stlawu.edu/~ecianc91/ or call 315-229-7548 for more information. War and Peace is an Umbrage Editions exhibition. Curator: Nan Richardson; Associate Curator: Lesley A. Martin; Director of Exhibitions: Launa Beuhler. top of pageSignlanguage:

[Viggo Mortensen] is photographer, painter and poet; a triple-time eye/I who shares with us the desire for the perfect as never more than an elusive glimpse of something that surprises us all. It seems that these moments can only be held if they appear to be escaping or yielding to what cannot last. Photography, whatever else it may be, is a focusing on detail. Mortensen likes sotto voce details; he gives his attention to instants that would otherwise have passed by unobserved, or more significantly, unregistered—things that in a literal sense were simply there for him because he was there for them—things that would have easily passed by as all else passes by, as we ourselves finally do. Mortensen seems to suggest that all incidents are photographable; perhaps none carry more significance than any others, or they carry the overwhelming significance he has given them through his involvement. It is a matter of being involved, being present, being, as Pollock might have said, “in it,” in what is happening, trusting it. He returns us to the subject as a connection through which life passes. We form the event, selecting what seems significant to us, and in so doing we shape ourselves through the precise energy of our attentions. The things he photographs belong to him, are of him because they happened to him, and therein lies their coherence. - from “Viggo Mortensen: A

Life Tracking Itself” by Kevin Power

Hillside WE UNDERESTIMATE DAMAGE I REMEMBER MAKING PROMISES Apart YOU FOUND MY KEYS THIS TRIP IS IF I CAN’T TOUCH YOU YOU ASK THE UN-NAMED SHOULD WE SIDESTEP ONCE SAID I’D MISSED Viggo Mortensen graduated in 1980 from St. Lawrence University, where he majored in government and Spanish. Special thanks to Pilar Perez at Perceval Press and to Robert Mann and Irene Grassi at Robert Mann Gallery, New York, NY. The exhibition is supported by the Carlyle and Betty Barnes Endowment Fund. Note: The Gallery not be open on Friday, February 28 until the opening reception at 7:30 p.m. We will have special open hours on Saturday as follows: 10:00

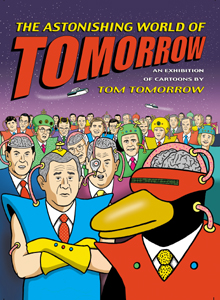

a.m. - 2:00 p.m. (open) The Astonishing World of Tom Tomorrow:

Compassionate conservatives; courageous Democrats; the war on terror/Iraq/whatever; homeland security; civil liberties; John Ashcroft; corporate crime; subversive penguins: pick any of the absurdities of the absurd times that we’re living through, and the odds are good that Tom Tomorrow has taken aim on them. With the help of Sparky the Penguin, alien Republicans with the face of Rush Limbaugh, a parallel earth on which a small cute dog was accidentally elected president, and actual quotes from fundamentalist terrorists of a different stripe (like Pat Robertson), Tom Tomorrow’s work lays bare the contradictions and idiocy at the roots of capitalism, politics, war, greed, consumerism, and patriotism—and it’s damn funny to boot. While there’s a certain comfort in calling Tom Tomorrow a political cartoonist, there’s also something lost in that designation. His work transcends the typical one-cell Op-Ed page cartoon, both stylistically and substantively. What other “political cartoonist” would use vintage action figures to critique social security reform, or cram several hundred words into a single cartoon in an attempt to clarify misconceptions about single payer healthcare systems? His frequently bizarre and always humorous off-kilter approaches give Tomorrow’s cartoons a depth that extends his parody and critique even further, making them all the more effective. We live in a political climate in which the once unthinkable is now commonplace. Orwellian Total Information Awareness schemes, a highly secretive executive branch with unprecedented power, and a president who declares crusades arguing that “you are either with us or with the terrorists” now mark the order of the day. It has become “un-American” and “unpatriotic” to question these developments, yet Tom Tomorrow continues on week after week, levying an effective, biting, and pointed critique of these new sacred American phenomena. In this sense, Tom Tomorrow is no mere political cartoonist. He’s a vital cultural critic and link to the common sense that we seem to have lost in declaring war on everything and everyone. -Robert Torres

After the Wall: Gender and Social Relations in

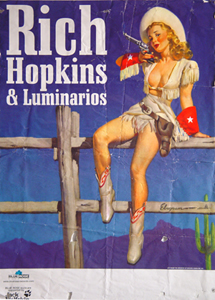

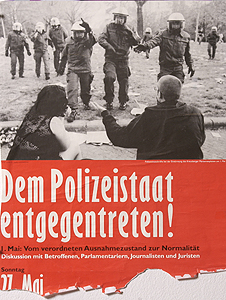

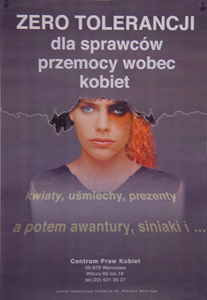

The posters and street ephemera on display in this exhibition were collected during four trips to central Europe since the summer of 2000. What began as mere curiosity for the odd flyer taped to a light pole became something of an obsession: I found myself roaming the streets of (east) Berlin, Prague, or Warsaw—streets that are, generally, far safer than the streets of American cities—in search of posters, flyers, announcements, advertisements, etc., whatever caught my eye. These were materials on their way to becoming rubbish; soon enough, every single object would be pulled down, covered over, thrown away, or scratched out. This was the ephemera of the street, visual texts cheaply produced and displayed, meant to draw the attention of passers-by to a coming event, a demonstration, concert, or performance; to an issue, problem or question of the day; to a product, apartment, or a body for sale or hire; or even to a lost cat. The transitory artifacts of popular culture are by their nature indicative of social change, and many of the objects chosen for this exhibition display gender as a prominent aspect of the massive social, economic, and political transformation still under way in post-communist Europe more than a decade after the end of the Cold War. In these texts, gender difference is variously displayed, encoded, and represented. For example, a street poster from (east) Germany advertises a band, “Rich Hopkins & Luminarios,” with a nostalgic play on the recent Cold War past featuring a come-hither image of a “cowgirl” in skimpy buckskin sitting atop a wooden fence rail. The desert setting suggests the American West, while the Soviet stars on the cowgirl’s wrists indicate that she can go both ways, ideologically speaking. Yet her blowing on a smoking gun suggests, too, a nostalgia for (hetero)sex, or perhaps, a sexist nostalgia, underwritten by the eroticized spectacle of the “Old West”/Hollywood cowgirl. On the other hand, sexism and its socially damaging effects form the explicit topic for other posters, including those from the Centrum Praw Kobiet (Women’s Rights Center) in Warsaw and other women’s and gender studies centers newly emergent in the region. Systematically ignored under the former communist regime, male violence against women is emphatically denounced in visually arresting posters such as “Zero tolerancji” (“Zero Tolerance”). In addition, the show includes works not immediately or explicitly about gender, such as “Dem Polizeistaat entgegentreten!” (“Oppose the police state!”), featuring a disturbing black-and-white photo of heavily armed German riot police bearing down on a young couple (and, it seems, on us). That one of those riot police may be a woman does not lessen the hyper-masculine quality of their state-sanctioned threat of violence. -Dr. Joel Morton, curator

Posters from Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic can be viewed on the Gallery’s Web site at http://www.stlawu.edu/gallery/eeursplash.htm. Special thanks to Marisa Zarczynski ’06 for her research assistance. Please contact the Gallery for information about this traveling exhibition.

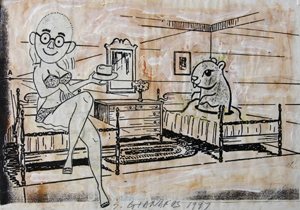

“To Whup Up On Sin”

I first heard about self-taught art while interning at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago during the summer of 2002. While there, I conducted research at a desk between two cavernous galleries and across from what I soon discovered was a black box theater for performances, screenings, and lectures. Given the size of the place and the scope of Intuit’s programs, I was surprised at how little I knew about this stuff. How did it correspond to other art forms I had studied in art history courses? At the time, I thought, “Wow, these people are crazy like Van Gogh!” Would Van Gogh be considered an outsider artist? Yes and no. During his lifetime, he was considered insane, his talent unrecognized, and yet today many regard his paintings as the pinnacle of high art. This exhibition, the result of an independent study course I am taking this semester, is comprised of fifteen drawings, paintings, and sculptures by six 20th-century African-American artists. Included are watercolors of dreamlike mountain scenes with floating eye/plant hybrids, glimmering mosaics depicting fantastical spirits, mythical representations of flying angels and demons, colorfully illustrated stories of the Apocalypse, and playful wood carvings of birds, horses, and famous or not-so-famous human figures. The artists use supplies that can be purchased at a local dime store, like crayons, colored pencils, glitter, or random, found objects like scrap metal, shovels, cans, and old furniture. Typically labeled visionary, divinely inspired, or obsessive, these artists have had no formal training and have worked outside of traditional institutions like museums and commercial galleries. You probably won’t find them discussing existential philosophy at Starbucks. Yet their deeply personal approaches reflect a range of life experiences, inner emotions, and fantasies. One artist, Sister Gertrude Morgan, a self-proclaimed “missionary and everlasting gospel teacher,” feels her Godly work can “whup up on sin,” which inspired the title of this exhibition. -Matthew Whitehead ‘03 Special thanks to Martha Watterson at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, Chicago, Illinois, and to Susann Craig, Jeff Cory, and Erik Weisenburger, lenders to the exhibition. Barnes Endowment Annual Juried Student Art Exhibition

Student artwork in all media, including drawing, painting, photography, sculpture, ceramics, and printmaking, will be presented in this exhibition organized by the Student Art Union and the Department of Fine Arts. The Annual Juried Student Art Exhibition is open to all St. Lawrence University students. Juried by Doug Schatz, assistant professor of sculpture at the State University of New York, Potsdam, the exhibition is supported by the Jeanne Scribner Cashin Endowment for Fine Arts and the Carlyle and Betty Barnes Endowment. Special thanks to Ashley Havens ’05. Gallery Hours All exhibitions and related educational programs are free and open to the public. The Gallery welcomes individuals and groups for guided tours; please call (315) 229-5174 for information. |