Exhibitions - Spring 2001

Ben + Todd: Recent Works

- January 21-February 16, 2001

- Related Educational Programs

Ben Grant: poured paint on commercial vinyl and laminated works on paper

Todd Matte: about me, misinformation, fully-stocked refrigerators, learning, breaking down-reorganizing-disorganizing space, Vietnam, simulacrum, the Arctic, Rauschenberg, a nuclear family, what it means to be working in a tradition, innuendos, refuse.

Male Gazing: Images of White Masculinity

from the Permanent Collection

Organized by Joel Morton, Assistant Professor of Gender Studies

- January 21 - February 16, 2001

- Related Educational Programs

from Portfolio II, 1932, gelatin

silver print, Gift of Albert Vaiser

through the Martin S. Ackerman Foundation, SLU 85.78

This exhibition invokes and redeploys the "male gaze" in order to subject images of white masculinity to our critical scrutiny. Long dominant in the history of Western art, the "male gaze" has made women, particularly the female nude, that which is looked at, scrutinized, and objectified. Male Gazing: Images of White Masculinity from the Permanent Collection contrasts traditional portraiture of elite white men with a wide range of artistic and popular images of white males, nude and otherwise. The exhibition de-mystifies the male gaze by transforming the conventional he-who-does-the-seeing into that which is seen. -JM

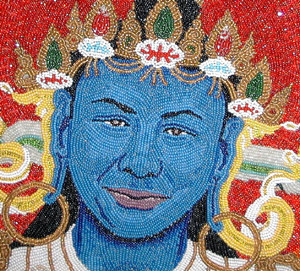

Every Bead A Prayer: Thangkas by Russell Ellis

- January 22-February 16, 2001

- Related Educational Programs

detail, beaded thangka

Russell Ellis spent his childhood as a military brat "touring the country," living on Air Force bases of the Strategic Air Command. Finally settling in Spokane, Washington, he finished high school and earned a degree in sociology at Eastern Washington State University. Anthropology and philosophy were his passions in college, as was eastern psychology. In the early 1970s, Tsultrim Allione, one of the first western women to take vows and become a Tibetan Buddhist nun, formally introduced Ellis to Tibetan Buddhism. He took refuge vows with His Holiness Karmapa and was taught by such lamas as Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Kalu Rinpoche, Nechun Rinpoche, and others.

In 1975, however, Ellis strayed from his spiritual path and was sentenced to federal prison for a drug conviction. There, he met his teachers in the art of beading. Cheyenne Big Crow was serving a sentence for his part in the Wounded Knee confrontation at the Pine Ridge Reservation. Jerry Peltier, cousin of Leonard Peltier, the noted Native American activist, also took Ellis under his wing and taught him beading techniques.

"I soon tired of beading on a loom or beading small rosettes on buckskin, so I decided to create a larger picture of some kind. Being a Tibetan Buddhist, I had a small postcard-sized image depicting the deity Tara, so I used that. My teacher, Trungpa Rinpoche, once told me, when I asked him how to develop patience, to simply repeat something 108,000 times. I decided to create a beaded thangka with at least 108,000 stitches, which is what dictated the size of my work. Each thangka is approximately fifteen square feet containing an estimated 450,000 beads." While beading, Ellis recites Buddhist mantras or prayers, and he estimates that each thangka has been empowered by at least three million of these prayers. Consisting of beads individually hand-stitched onto canvas, the thangkas take at least two thousand hours to complete. Ellis has been beading for over twenty-five years and has created seven thangkas to date.

beaded thangka

Vajradhara is seated on the lion throne holding a vajra or dorje, the symbol of his uncompromising compassion toward all sentient beings. In his other hand is a bell that symbolizes his ability to teach the dharma or path toward enlightenment. Karmapa, the lineage holder of the Kagyu line or school of Tibetan Buddhism is seated in the bottom right corner. To the left is Taisitupa, the lineage holder of the Nyingma line. In both schools of Tibetan Buddhism, Vajradhara is a realized master. The merging of the two is very profound, signifying tremendous spiritual power.

St. Lawrence University Festival of the Arts

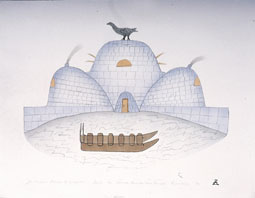

Power of Thought: The Prints of Jessie Oonark

Organized by Marie Bouchard

- February 21 - April 12, 2001

- Related Educational Programs

1977, screenprint on paper, 21 x 25 inches

Jessie Oonark, one of Canada's most important Inuit artists, began her artistic career when she was in her mid-fifties. Over a span of twenty years, Oonark made hundreds of drawings and textile works. Her interest in art was recognized early, and her drawings were the first works from Baker Lake to be made into prints by the Cape Dorset print shop in 1960 and 1961 and were featured in each of the Baker Lake Annual Print Collections catalogues from 1970 to 1985. She was elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and later recognized as a Companion to the Order of Canada. Oonark's work was featured in numerous group exhibitions in Canada and internationally, and in 1986, she was honored posthumously with a solo retrospective at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in Manitoba.

Through her art, Oonark was able to explore and re-invent many facets of her life--living on the land and the traditional activities, mythology, intellectual culture, and environment that shaped her artistic vision. The transition from nomadic life to life in the settlements set the stage for a new beginning as an artist. The prints in the exhibition reflect Oonark's personal journey, the psychological soul travel that allowed her to intellectualize and explore the complex cross-cultural and social relationships that marked Inuit life at that time.

Oonark's sophisticated visual imagery is most forcefully and clearly expressed in the print medium. The strong central images and bold designs that characterize her textiles form some of her most successful images when isolated on the printed page. Unlike the Cape Dorset artists who faithfully reproduced her drawings into prints, the Baker Lake printmakers worked cooperatively to interpret the artist's images, utilizing a strategic use of space, economy of line, and exaggerated color palette. Prints such as Young Woman (1971) and Big Woman (1974), which were cover designs for the Baker Lake Annual Print Collection catalogues, exemplify the clarity of style and bold shapes that characterize Oonark's work. The prints also reflect Oonark's preoccupation with the role and importance of women in Inuit society. The ulu, an essential crescent-shaped knife used predominately by women, is used repeatedly by the artist as a design motif symbolic of womanhood.

Oonark freely explored spiritual aspects of Inuit culture, giving visual expression to subjects that had been prohibited by missionaries and others. Helped by Spirits (1970), Lake Spirits Laughing at Stranded Man (1976), and Flying Woman (1978) all refer to the traditional belief systems. Although she was a devout Anglican, Oonark frequently juxtaposed Christian images with images of shamanism, animism, and the world of spirits. In addition, daily life is represented in Drying Fish (1970) and Hunting with Bow and Spear (1975), and the importance of family is seen in Favourite Daughter (1985). Oonark is perhaps most inventive in her portrayal of the close relationship between people and animals. Prints such as lqaluk Uluk (1978), Fish with Ulus (1981), and The Catch (1984) display the intimacy of this symbiotic relationship.

Power of Thought (1977) and Tarrara (Seeing Myself) (1981) are perhaps more overt attempts by the artist to probe metaphysical issues, such as being, identity, time, and space, that would have concerned her as an artist living and working in a time of tremendous social and cultural upheaval. This intellectual introspection informs much of Oonark's imagery. Current research indicates that 108 prints by Oonark were created from 1970 to 1985. The exhibition features forty prints based on drawings and textiles of Jessie Oonark produced by Baker Lake printmakers as well as a few of her unreleased prints. The exhibition, Power of Thought: The Prints of Jessie Oonark, named after her screenprint of the same title, provides the first in-depth analysis of the artist's prints. -MB

The exhibition and national tour are organized by the Marsh Art Gallery, University of Richmond Museums, Virginia. Guest curated by Marie Bouchard, the exhibition features prints lent courtesy of Judith Varney Burch, Arctic Inuit Art, Richmond, Virginia.

Arctic Dreams and Nightmares

Drawings and Cartoons by Alootook Ipellie

- February 21 - April 12, 2001

- Related Educational Programs

ca. 1993, pen and ink on paper

Alootook Ipellie was born in a camp near Iqaluit (formerly Frobisher Bay), the capital of Nunavut, where he spent his childhood and teenage years experiencing the transition from a traditional nomadic Inuit way of life to life in government-sponsored Inuit village settlements. In 1973, after a short stint as an announcer and producer for CBC Radio in Iqaluit, he moved to Ottawa to study and pursue a career in art. He has since become a noted artist and central figure in the Inuit literature movement. Ipellie is the former editor of Inuit Today, published by the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada, and Inuit, published by the Inuit Circumpolar Conference. His essays, stories, and poetry have been featured in Northern Voices: Inuit Writing in English (University of Toronto Press, 1988) and An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English (Oxford University Press, 1998), and his artwork has been exhibited in Canada and Greenland. Ipellie notes, "I've always thought writing and storytelling were means of exploring some parts of truth about human nature, and that stories need to be told or written in order to understand ourselves better. They are essentially tools we use to help express our 'silent voice' within our conscious or unconscious minds. Writing and storytelling allow us to escape our own predicaments in this physical world and free our minds to go beyond it."

Inuit Art from St. Lawrence University's

Permanent Collection and Regional Lenders

- February 21 - April 12, 2001

- Related Educational Programs

stencil on paper, ed. 37/50, 19 5/8 x 25 inches, SLU 2000.33.1

A selection of Inuit prints, carvings, and drawings will be presented with accompanying text panels written by students in Cultural Encounters 212 Creative Expressions of Healing. Several prints and carvings from Cape Dorset and Pangnirtung will be shown, as will recent sketches and studies by Mary Pudlat of Cape Dorset.

Inuit of the Arctic: Hunters of the Spirit

Photographs by Alison Wright

- February 21 - April 12, 2001

- Related Educational Programs

2000, color photograph

Layers of change challenge the spirit of Inuit people today. Tenacious in their attitude toward life in such desolate and harsh conditions, the Inuit now use tools of legislation and language rather than rifles and dog sleds. I spent just over three weeks in Nunavut last fall, and I feel honored to have been a witness to the creativity and demands of daily life of the Inuit.

There are particular challenges involved as I decide how to represent indigenous cultures. My work documenting Tibetans in exile has been my most intimate work to date, yet was twelve years in the making. Although I always read and study as much as I can about a place before and after I go, I never really know how people will react until I meet them. Recently, while photographing hill tribes in Southeast Asia, I was chased and beaten by a few Akha in Laos, yet welcomed by Hmong living in the same area. I later discovered that many westerners the Akha had encountered previously were looking to smoke opium. Often the cultural insensitivities of others can pave a difficult path before I even get there.

Of course, personality plays a role in how one works. Is it my choice to portray smiling people, or is this simply a natural response to our interaction? I used to admire burly photographers loaded with gear, but as a diminutive woman, I've learned the advantages of appearing approachable and non-threatening. I use my camera as a tool for getting to know and learn about others. In my photographs, I construct environmental portraits of my subjects and hope to create real connections with them. -AW

Barnes Endowment Annual Juried Student Art Exhibition

- April 26 - June 4, 2001

Student artwork in all media, including drawing, painting, photography, sculpture, ceramics, and printmaking, will be presented in this exhibition organized by the Student Art Union and the Department of Fine Arts. The Annual Juried Student Art Exhibition, open to all St. Lawrence University students, is the annual Barnes Endowment Exhibition, with additional funding provided by the Jeanne Scribner Cashin Endowment for Fine Arts.

All exhibitions and related educational programs are free and open to the public. The Gallery welcomes individuals and groups for guided tours; please call (315) 229-5174 for information.

| Gallery hours | |

| Monday-Thursday Friday and Saturday |

12-8 p.m. 12-5 p.m. |

top of page