Exhibitions - Fall 2005

|

|

|

|

|

|

October 6 - November 3 |

Homeland.Wonderland: Drawings by Chika Okeke-Agulu and Marcia Kure |

November 10 - December 10 |

|

|

|

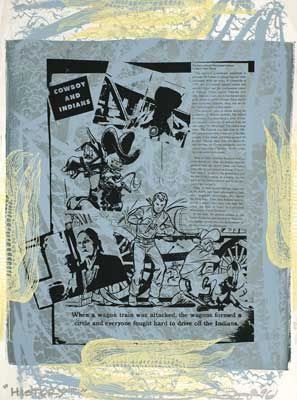

| Following in

the Footsteps of our Ancestors: An Exhibition of Hotinonshonni Contemporary Art

This exhibition is the result of collaborative efforts among the Salmon River Central School District and the Akwesasne Cultural Center on the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation in northern New York and St. Lawrence University—partners in Teaching American History Through Hotinonshonni Eyes, a three-year program funded by the U.S. Department of Education. “Hotinonshonni” is an Onondaga term that refers to the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. The program allows teachers in New York State schools with significant Hotinonshonni populations to explore the ways in which the Hotinonshonni have influenced and been influenced by American history, and how they envision their hopes for the future. According to Katsitsionni Fox and Sue Ellen Herne, two of the program leaders and curators of this exhibition, Hotinonshonni students are often disaffected by the teaching of American history because traditional Native history is not respected in the classroom. Most schoolteachers are not familiar with Native American history, and knowledge that students have learned through their families’ oral histories is often discounted, rather than used to spark classroom discussions. The American History Through Hotinonshonni Eyes program will help teachers develop lesson plans and materials with which to teach Native and non-Native students. The Hotinonshonni artists in the exhibition were asked to submit works that examine and critique history using the language of contemporary art, and to reflect on how they were able to stay true to the path of their ancestors. How did the artists find ways to reinforce Hotinonshonni teachings, history, and culture while attending institutions that were built by what is essentially a colonizing culture? For some, the answer is that they did not receive support and were forced to look elsewhere. Though the artists address difficult questions and topics, the grant program and exhibition are at heart filled with hope and passion.

Artists

Katsitsionni Fox teaches Native Studies and Native Film at Salmon River Central School, and her work invigorates the lives of many Hotinonshonni students. As the program coordinator at the Akwesasne Cultural Center, Sue Ellen Herne works to promote respect for the diversity within and outside the Native community.

Far North:

As a youngster reading the books of Arctic explorer Peter Freuchen and leafing through old National Geographic magazines in my grandparents’ library, I was fascinated by the far North, and a trip to that part of North America had always been high on my list of places to visit. Over the years, I’ve acquired a few carvings by Alaskan natives, but lately I’ve been exposed to the stone carvings, drawings and prints of Cape Dorset and Baker Lake. With the gentle prodding of friends and through their contacts, I made plans to travel to Baffin Island in the summer of 2004. As I flew from Ottawa north to Iqaluit, the land became treeless. Small floes of sea ice and remnants of deep snowdrifts from the previous winter were still evident. My aim was to meet Inuit artists and to get out on the land with guides to learn more about the region and its inhabitants. I especially wanted to understand how the environment influenced the people and their art. During the Vietnam war, I had been stationed in the Aleutian Islands, a treeless area, but I was not prepared for the endless expanse of barren ground that I encountered first by plane, then on the ground and from the sea. Life in Cape Dorset is basic and isolated. Everyone in the North lives according to nature, and there are no exceptions. Away from the settlement, a walk to the old campsites makes clear what life was like only a half century ago: wooden tent frames, stone food caches and fox traps, inuksuit or stone cairns, the justice circle, and bleached caribou antlers are revealed in the landscape. Light and darkness, rock and gravel, land animals, sea creatures and birds, fire, water and ice—all mark life in the North. The art from the West Baffin Eskimo Co-op and by individual artists I met incorporated these fundamental ingredients. The homes of stone carvers are obvious with rock chips and stone dust piled by the base of their large wooden utility spool tables. A visit to the co-op’s print shops and a stonecut print demonstration taught this neophyte some of the technical aspects of the printing process. I’ve always considered indigenous people to be natural artists due to their relationship to the land, and my experience in Cape Dorset reinforced this. In the settlement, sharp juxtapositions are created between the old and the modern: young mothers carrying their babies in the hoods of light summer parkas or amautiks, and kids in hip-hop clothing listening to iPods; sledges and snowmobiles; dog teams kept on small islands offshore for the summer; square-sterned, motor-powered canoes for weekend trips to outlying camps; and the constant presence of discarded plastic bags and soda cans from the general stores set against the pristine wilderness. An elemental starkness in the artwork from Cape Dorset may be derived from sharply honed strategies of survival devised over many centuries. And yet, in addition to traditional representations of the natural environment, other facets of modern daily life, such as airplanes and snowmobiles, are now incorporated in prints, drawings, and stone carvings. -Allan

P. Newell

Special thanks to Allan P. Newell, St. Lawrence University trustee, and Dorset Fine Arts,Toronto, Ontario. Cloth Only Wears to

Shreds:

In Yoruba culture and religion, the significance of cloth goes beyond body covering to express a rich and profound belief system. In its creation, the color, weave and design of cloth reflect the aesthetic sensibilities and character of the artist and of the future owner. Extensive use of opulent materials in a garment conveys the power and authority of the wearer. Cloth not only defines the identity of the individual and family, but also evokes the ancestors, thus creating a metaphorical link between the living and the dead. Fabric, which the Yoruba believe outlives its owner, can disintegrate but cannot disappear from the material world. “Cloth only wears to shreds”—a refrain from an Ifa divination verse—refers to this deathless, eternal quality. The textiles and garments, which elucidate the artistry, technology and ideas behind their creation, were selected for this exhibition from a vast and unique body of Yoruba material, some 160 textiles and ritual objects produced in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Examples of resist-dyed, hand-woven, silkscreened and machine-printed textiles are presented, including women’s adire cloth—dark indigo cotton with bold or subtle patterns in light blue. The vivid spectacle of color, texture and movement represented in the exhibition is the result of the life’s work of Uli Beier, who first recognized and promoted textiles as a major form of Yoruba artistry and cultural expression. The accompanying black-and-white photographs feature Beier’s compelling portraits of Yoruba chiefs, dancers, and others. -from

essays by Jill Meredith and John Pemberton III

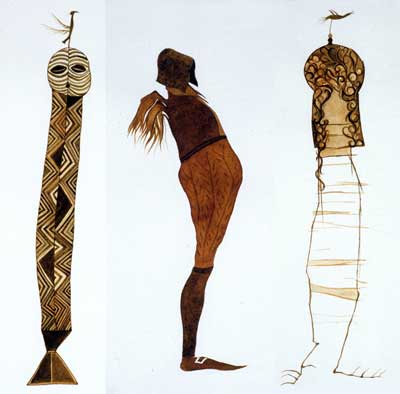

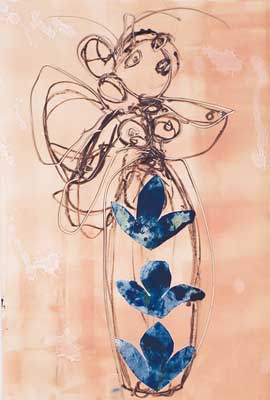

Homeland.Wonderland:

My poems reflect upon events in both Nigeria (Homeland) and the United States (Wonderland). As might become obvious, many of the artworks—Marcia’s and mine—are meditations or statements on specific social and political experiences and phenomena, particularly those associated with war and military dictatorship. As such, the poems speak to the concerns and themes of most of my own work and some of Marcia’s. Of course, poetry may not always be the best medium for explaining visual art, but it adds a new layer of reading and understanding to the images. -Chika Okeke-Agulu

The artists' lecture is partially funded by the Jeanne Scribner Cashin Endowment for Fine Arts; special thanks to Obiora Udechukwu, Dana professor and chair of fine arts at St. Lawrence University.

fac•ul•ty [1350-1400; Middle English faculte < from Anglo-French, Middle French < Latin facultat- (s. of facultas) ability, power, equiv. to facil(is) easy.] Any of the powers or capacities possessed by the human mind.

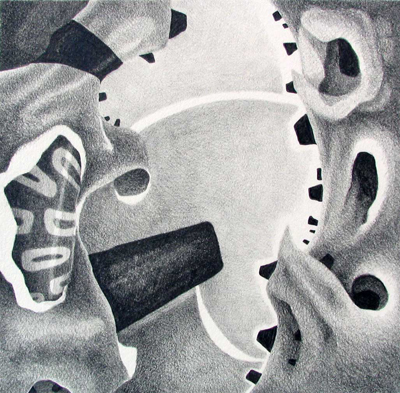

We are a diverse group of individuals connected by our desire and need to express ourselves. We are from different parts of the world and have traveled around the globe. We have reared families, worked for social justice, volunteered at homeless shelters, worked at awful summer jobs, and raised adorable pets (mostly cats). We write poetry, sail, hunt, cook, listen to music, hike, read 20 books a year, watch bad TV, drive 80 miles for a cup of good coffee, eat organic food (and even an occasional Oreo), go to museums, spend too much time on the Internet, and try to make sense of economic indicators and global warming—just like you.

We make sense of this crazy, beautiful world through art. We paint, draw, print, collage, photograph, morph, videotape, cut, paste, sew, change, adapt, and start over. And over. When we think we get it right, we start the process again. And again. The finished product is not what motivates (my) artwork. The process of creation is what drives my life and artistic production (Craig). We find inspiration in things big and small, organic and man-made, and in political and social issues. We create works that are literal or that manifest themselves into new realities, different from their sources, yet still maintaining an essence of their origins (Schulenberg). This quest for visual thrills and beautiful mysteries is an evolving scavenger hunt, a constant adventure (Strauss). We find beauty in the varied colors of skin, fabrics, and landscapes of different countries (Serio) and strive to develop clarity of vision accompanied inevitably by a certain lucidity of expression (Udechukwu).

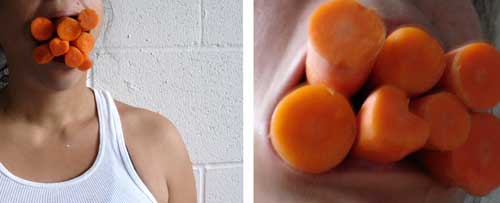

I was born in 1984. It has been a short but exciting life. Sometimes when I was touring with my post-punk band, Amy and the Angry Inch (now defunct), I would think back to the painful experience that my mother had to endure, giving birth to a daughter who was bigger than herself. My own body, from that first day that I entered the world, has been filled with nothing but heart-shaped Mexican jumping beans, and for that reason I feel fortunate that my best friends Cherry Rabbit, Speed Racer, Penny the Pug, and numerous imaginary artists were there to help me as I was growing up and trying to understand the world. Often plagued by a sense that I am walking through a dream, here but not really here, I have always been prone to imagination for comfort. When flying a kite in Chicago with my father and brother, I remember feeling like the kite against the blue sky and like the car door I sat next to as we drove away, and like the wind, and then I knew that I could remove myself from any experience. Soon enough I realized that beautiful cakes had a special aesthetic significance in my life and that if I focused on the colorful flowers and sugary sweet memories they would soon hold, then I could also be walking a tightrope from my bedroom window to the neighbor’s bedroom window. In that bedroom, I could be an entirely different floaty somebody. From there, I could tightrope-walk to another room down the street and watch television with the family there. I never found a way to enjoy the TV dinners they ate, but marveled at the compartmentalized packaging, wishing my bed was a huge aluminum, form-fitted compartment just for my Mexican jumping bean body. When my heart filled my throat, then I could shut the shiny aluminum lid and push my heart back down to where it should be. -amy hauber

Amy Hauber is an artist and educator residing in Canton, N.Y., where she is an assistant professor of fine arts at St. Lawrence University. She teaches sculpture, ceramic sculpture and foundations, with an emphasis on cross-disciplinary/inter-media studies in all three areas. Born in Chicago and transplanted many times before landing at the age of twelve in her parents’ hometown of Pittsburgh, Pa., Hauber studied information science, English writing, and fine arts at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University before receiving her MFA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She has also taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design and Carnegie Mellon University. Working across media disciplines, her research interests include collaboration; digital, material and sex culture; and the construction of morality, identity and aesthetics in contemporary society. Hauber has twice been a resident

artist in the John Michael Kohler Arts Center's ARTS/Industry program

and was awarded an honorary fellowship from the University

of Wisconsin-Madison.

She has exhibited her work nationally and is represented

in Chicago by Western Exhibitions. Hauber’s ceramic-based

objects were featured in American Craft Magazine:

Portfolio Amy Hauber, December/January 2002.

Untold Stories of My

Present, Past, and Dreamtime:

I am Navajo/Dine of the Salt and Bitter Water clans. I grew up on a Navajo reservation in northeastern Arizona and began traveling at an early age with my family. At various times in my childhood, we traveled across the United States and into Mexico, which helped me look past the boundaries of the reservation and become curious about what was happening beyond the sacred mountains. The process or medium I use in my work depends on the statement or idea I am exploring. Lately, the images are about transformation, womanhood, and the role of animals in my life. These symbols/images are linked to my travels. Since 1995, I have formed strong relations with Maori artists in New Zealand, and completed my sixth visit there last January. I have also collaborated for over eight years with Siberian artists from the Amur River region of Russia, but they speak very little English, which makes communication difficult. In the summer of 1999, I taught printmaking at the Pont-Aven School of Contemporary Art in France, and returned in 2004 to keep connections open with the Bretons I met there. I am able to use all of these experiences to tell stories in my artwork. Much of the history of other nations overlaps with my people’s history. Meeting people from different cultures has grown to be a major part of my life. I am currently working with an artist from Lebanon on a printmaking project that will travel to the Middle East. Other prints are currently in Northern Ireland, South Africa and Bulgaria. I was brought up as a traditional Navajo, and respect for self and others has always been important to my people. Western influences have also made me who I am today. I am proud to be Navajo/Dine. I hold only my story and by no means speak for all Native peoples.

The exhibition and lecture are funded in

part by the Barnes Endowment Fund and the Jeanne Scribner

Cashin Endowment Fund. Special thanks to Melissa Schulenberg,

assistant professor of fine arts. Gallery Hours All exhibitions and related educational programs are free and open to the public. The Gallery welcomes individuals and groups for guided tours; please call (315) 229-5174 for information.

|

||

| top of page |